In 2024, the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) is looking at geographic locations where Japanese Canadians lived after migrating to Canada, since the 1800s, and where they were interned/incarcerated in 1942.

The Story of Cumberland and Royston

By Lorene Oikawa, Past President NAJC

In the sweep of the eastern shoreline of Vancouver Island from Kelsey Bay in the north and down to the south including Hornby and Denby Island, this is “the land of plenty.” K’όmoks peoples have been the care takers of “the land of plenty” since time immemorial. Local food sources came from the sea and land. The European settlers took the land and resources of the K’όmoks peoples and forced them south.

Cumberland (formerly known as Union) is one of the settler towns in the Comox Valley, about a 1.5 hour drive from Nanaimo and about 10 minutes from Courtenay. For centuries, the K’όmoks peoples were the only humans in the area who knew the forests, and where to hunt for food from the land and sea. They did notice the shiny black deposits which would eventually attract European settlers, and then workers from China and Japan. The trees in the forests were cut down for log shelters and then houses. Coal mines are first developed in the 1860s and 1870s by the Union Colliery Company who eventually sell their rights to the Dunsmuir family.

Miners fill their carts with coal and are paid less than 60 cents per ton. If there is more than 65 pounds of waste rock, then the miner is not paid. Japanese Canadian and Chinese Canadian miners were paid about half of the rate that white miners were paid. By 1897, Cumberland was producing 700 to 1000 tons of coal per day with about 600 workers in the general population of 3,000.

Discrimination against Asian miners didn’t stop when they died. They weren’t allowed to be buried in the city cemetery with the other miners. There were separate cemeteries for Japanese Canadians and Chinese Canadians.

Asian Canadians were also working in Union Bay. Japanese Canadian workers stoked the coke ovens and shoveled out the coal dust from coke ovens. Indo Canadian workers were building the docks and Chinese Canadian workers were working as trimmers on the coal ships.

Mining is dangerous work and particularly on Vancouver Island. The conditions were harsh. Workers would have to work bent over in narrow coal seams for 8 to 10 hours. Vancouver Island mines were known to have a lot of toxic methane gas. Miners wore soft peaked caps with “tea kettles, “tiny oil lamps clipped to their caps. The flames could ignite methane gas in the mines and there was always a risk because of matches and the accumulation of coal dust in the air. Some experienced miners from England were shocked to find the continued use of “open flame” lamps. One statistic from that time is that of 1,000 mining accident deaths on Vancouver Island, 295 died in Cumberland.

Mining is dangerous work and particularly on Vancouver Island. The conditions were harsh. Workers would have to work bent over in narrow coal seams for 8 to 10 hours. Vancouver Island mines were known to have a lot of toxic methane gas. Miners wore soft peaked caps with “tea kettles, “tiny oil lamps clipped to their caps. The flames could ignite methane gas in the mines and there was always a risk because of matches and the accumulation of coal dust in the air. Some experienced miners from England were shocked to find the continued use of “open flame” lamps. One statistic from that time is that of 1,000 mining accident deaths on Vancouver Island, 295 died in Cumberland.

The 1912-1914 Big Strike on Vancouver Island was started because of the unsafe working conditions. The miners fought back against the violent union-busting of coal baron James Dunsmuir. In 1918, one vocal union leader Albert “Ginger” Goodwin was targeted and murdered. His funeral procession stretched over a mile long with a couple of thousand people participating and ignited a one-day general strike in Vancouver.

Japanese Canadian settlers first settled on leased land near the mines in Cumberland where they worked. Land near No. 1 mine was referred to as No. 1 Town and the area near No. 5 mine was referred to as No. 5 Town. This reflects the race-based segregation that took place.

No. 1 Town and No. 5 Town comprise the largest Japanese Canadian community on Vancouver Island. There were about 600 Japanese Canadians.

In No. 1 Town, there were about 36 houses for families. There were also community vegetable gardens, two general stores, a town hall, a language school, and a bath house. To the east was a coal tailings pile known as Taka Yama. It formed a backstop for a baseball diamond in the open space. Baseball was (and continues to be) a popular sport for Japanese Canadians.

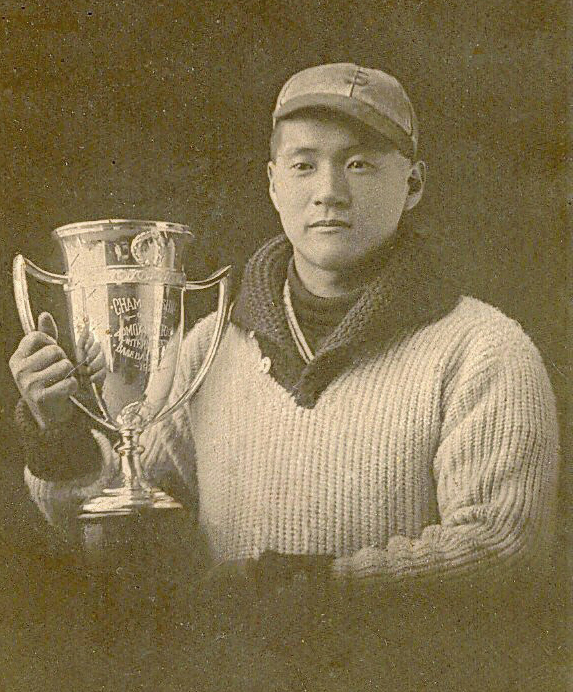

George Doi who was a boy in Royston (about 2 miles east of Cumberland) said that everyone liked baseball and he remembered families heading to Cumberland with a basket of food to watch the games. The baseball team for No. 5 Town was called “Sun” and the baseball team for No. 1 Town was called “Nippon.” His father, my grandfather, Kenichi Doi was born in Cumberland, lived near No. 5 Town, and played for the Sun team.

The Vancouver Asahi baseball team came to play in Cumberland in the 1920s and recruited Kenichi. He went to Vancouver and worked in local mills and played for the Vancouver Asahi baseball team when they won the 1926 Terminal League Championship. However, the pull of family was too strong. He left Vancouver to get married and then stayed to help the family when their home was lost in a fire that took out 26 homes at No. 5 Town. The family moved to Royston, and he played for the Royston baseball team.

There was a traditional tea garden at Comox Lake from 1914 to 1939 where women spent some time, but most of their time was spent looking after their families. They had traditional duties including gathering and growing food and preparing meals.

George Doi shared the story of his mother [my grandmother], Sumiko Doi. “Mom went clam digging frequently. I don’t know the names of all the clams we picked, but one of my favourites was the horse clam (midget geoducks?). Mom used to salt them and string them up to dry, just like dried cuttle fish…we would tear off strips and eat them like candies. They really were finger licking good!”

“Mom was the first to find edible seaweed in Royston. I don’t know at which beach she found them, but word got around really fast and soon everybody was out in the salt chuck picking seaweed. They washed and cleaned them and hung them up to dry before using them in soups and other foodstuff.”

As the Japanese Canadian community grew, they become established, buying land in Cumberland, Royston, and Bevan, and building their homes. Some entrepreneurs start businesses such as Iwasa General Store and the Japanese Canadian owned and operated Royston Lumber Company that logged and ran a sawmill. The sawmill had about 100 workers and its own railway which transported logs to the mill. The mill produced about 45,000 board feet of lumber per day. Japanese Canadian families lived in about 22 residences at the site of the mill which also included a Buddhist Temple, Japanese language school, and community hall.

Racist provincial legislation introduced in the 1920s started restrictions for Asian Canadian workers. In 1922 legislation prohibits work in pulp and paper mills and in 1923, the Oriental Exclusion Act prohibits working underground. In 1927, the Japanese Canadian houses at No. 5 Town are wiped out by a fire. Many Japanese Canadians turn to logging and get work at the sawmill. The entrepreneurial spirit prevails, and some Japanese Canadians start selling groceries, hardware, and opening tailor shops.

In 1930, the Royston Buddhist Church is built and provides an outlet for religious services and cultural events such as plays and festive events such as Hana matsuri. Japanese Canadians from Cumberland, Courtenay, Union Bay, and Comox attend as well as children who attend the Japanese Language School and other members of the community who are welcome to attend the cultural events.

In the early 1940s, Japanese Canadian children make up a third of the students in elementary school and about half in the high school in Cumberland. Japanese Canadian children also attend Japanese language school so are in school six days per week. Florence Bell said she showed up to her elementary class one morning and her best friend Mae Doi [my mother] and all the other Japanese Canadian kids were gone. No one could explain their disappearance.

On April 15, 1942, about 600 Japanese Canadians, babies to seniors are forcibly removed from Cumberland and Royston. In a devastating act of racism by the Canadian government, Canadians of Japanese ancestry are deemed enemy aliens despite a lack of evidence. They are sent to Hastings Park and then eventually to internment/incarceration sites. Their homes, properties, businesses, and possessions are taken. They, along with the rest of the about 22,000 Japanese Canadians, would not be released until 1949, four years after the end of the Second World War.