Highlights of October Dates in Japanese Canadian History

By Lorene Oikawa, Past President NAJC

In 2023, the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) is reviewing the highlights of dates for each month, from the period 1941 to 1949. We are looking at the actions of government and the impact on Japanese Canadians.

October 1940 – A special committee was convened by the government to look at what they deemed the hostility between the white and Japanese Canadian populations. The committee’s task was to determine if there were risks to security. They heard from 57 witnesses which included only 8 Japanese Canadians, high ranking officials from the BC government and military, and representatives from the anti-Japanese movement. This happened outside of the date range the NAJC is reviewing. However, this is significant because of the declaration of various police representatives who said they did not find any evidence of “subversive acts” over a period of years. Ken Adachi reports in his book, The Enemy That Never Was, that “they [police] said, the Japanese had “an admirable record as law-abiding and decently behaved citizens.””

October 1942 – Japanese Canadians at incarceration/internment camps in the Slocan Valley were allowed to organize a Victory Bond drive. This was an exception because organizing by Japanese Canadians was not something that would be usually allowed, but this was one event that the Security Commission could not refuse. Most of the Japanese Canadians were born in Canada and wanted to show what they could do for their country. They created a strong organizational system and developed relationships with the people in the community. Soon, the churches opened their doors to fund-raising events, and for schools to be held in the basements. The Security Commission saw that there wasn’t any local opposition to this type of organizing and the benefits, so they allowed Japanese Canadian committees to be formed in the camps.

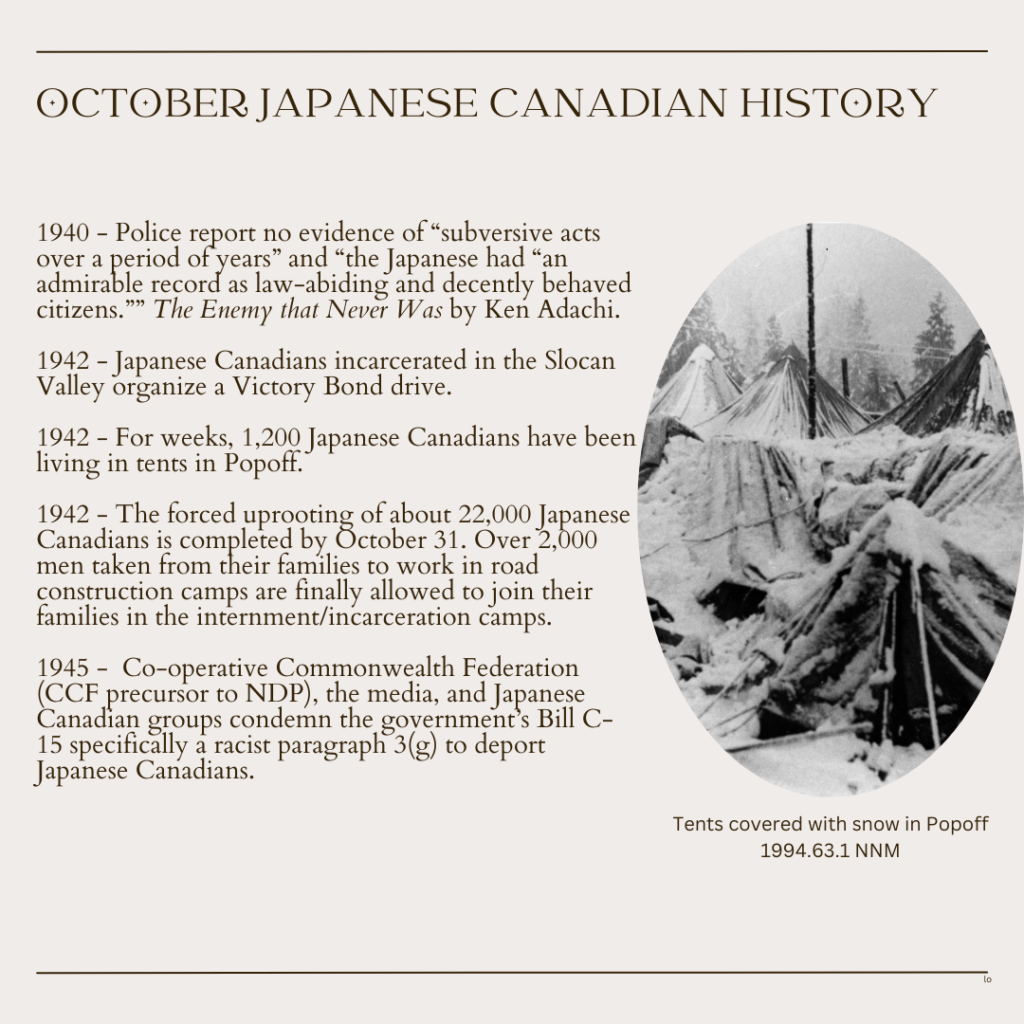

Mid October 1942 – For weeks, 1,200 Japanese Canadians have been living in tents in Popoff. With 24 hours notice and no information, Japanese Canadians were forced to leave their homes with a few suitcases and no warning of the conditions they would face. Many survivors talk about the cold and ice on the inside of the tent. Mae Oikawa (née Doi): “We arrived in Popoff and had to live in a tent: my parents and six children in a tent. It was very, very cold. We didn’t have a mattress. We had two blankets right on the ground. We weren’t told to dress warm. Mom told me to wear all my clothes in layers, but I was still cold. I don’t know how I survived.”

The BC Security Commission decided to send Japanese Canadians to small towns in the Kootenays, so-called ghost towns, because of the derelict buildings from their boom times. However, even with the forced labour of over 1,000 Japanese Canadian trades people repairing buildings in the spring, there wasn’t enough space.

Hastily constructed shacks with green (fresh cut) lumber resulted in shrinkage creating gaps in the walls which let in cold air. And there weren’t enough shacks for everyone so others were forced to live in tents.

In the late 1800s, these small towns were bustling with people and money. Slocan had about 12 hotels and a population of about 1,500. Sandon had 29 hotels and 5,000 residents, although some say the population was about 10,000 at its peak. When the ore disappeared so did the people and the businesses. When Japanese Canadians were forced into Slocan in 1942, the population was about 200. Sandon had 50 residents. New Denver had about 350 residents. When 1,200 Japanese Canadians moved into Kaslo, they easily tripled the population. New Denver’s populations swelled to over 2,000. Sandon was over 1,000. The Slocan Valley which includes Slocan, Bay Farm, Popoff, and Lemon Creek held about 4,800 Japanese Canadians comprising 25% of the population of six camps in the interior of BC.

Greenwood’s mayor wanted to revive his town of about 200 people, so he welcomed 1,200 Japanese Canadians. This was not the general feeling of the communities, but the influx of Japanese Canadians meant sudden profits for local businesses and the small towns soon realized that the Japanese Canadians provided a huge boost to their local economy.

October 31, 1942 – The forced uprooting that was ordered in February was not completed until October 31. This was about eleven months after the start of World War 2. The slow proceedings are a good indicator that the government didn’t have any real fear of the Japanese Canadians they were uprooting. The over 2,000 men who had been taken from their families earlier in the year, between March and June, and forced into road construction camps were allowed to join their families in October.

October 1945 – CCF (Co-operative Commonwealth Federation precursor to the New Democratic Party, NDP), the media, Japanese Canadian groups, and churches condemn the government’s Bill C-15 specifically a racist paragraph 3(g) allowing the federal government to “deport” Japanese Canadians. Deport is in quotes because Canadian citizens can not be deported unless their citizenship is revoked.

The federal government had tried to quietly slip the clause into Bill 15, National Emergency Transitional Powers Act which was introduced on October 5. The Second World War ended on September 2, 1945. The War Measures Act which gave the federal government the emergency power during war time to suspend the rights and liberties of Japanese Canadians would expire by the end of the year. Clause G would allow the federal government to continue to control the entry, exclusion, deportation, and revocation of citizenship. This would allow the government to continue the forced removal of Japanese Canadians, but it would also be a threat against any other group of people.

In mid-October the paragraph 3(g) caught the attention of people. There was a huge outcry by the CCF and the media and others. The only voices who vigorously supported the Bill were the BC Liberal and Conservative Members of Parliament. They pulled out the same ugly rhetoric and lies they had been using for years smearing the reputation of Japanese Canadians. The CCF pointed out the facts that no Japanese Canadian was charged or convicted. We also know that the government carried out the racist act of uprooting, dispossession, incarceration and exile, disregarding reports from the police and the Canadian military who told them there wasn’t any evidence against Japanese Canadians and no action was required.

The paragraph was removed in response to the publicity and pushback, and the bill was passed in December.

Unfortunately, section 4 of the bill did not receive attention. Section 4 allowed for all Orders-in-Council (OIC) under the War Measures Act to be extended for one year. All that was needed was to pass an OIC under the War Measures Act before it expired on January 1, 1946.

The federal government continued to manipulate the system and Japanese Canadians would not be free until 1949, four years after the Second World War ended.