Welcome to the new NAJC National Executive Board. The acclamation took place at the NAJC Annual General Meeting on September 23, 2022.

Les Kojima President

Naomi Katsumi Secretary

Maryka Omatsu Director

Judy Hanazawa Director

Yukari Peerless Director

Alex Okuda-Rayfuse Director

Susanne Tabata Director

Lorene Oikawa Past President

Staff

Kevin Okabe Executive Director

The National Executive Board will be continuing the important work on initiatives to support the Japanese Canadian community across Canada. Our communications will continue through various channels such as The Bulletin, Nikkei Voice, the NAJC website najc.ca our e-news (sign up at https://najc.ca/subscribe) and social media.

October 18 Persons Day in Canada

by Lorene Oikawa, NAJC Past President

October 18 is Persons Day in Canada https://bit.ly/3yCBg85 It falls within the month of October and 2022 marks the 30th anniversary of Women’s History Month in Canada. This commemoration provides another opportunity to seek out the stories of women who are not usually reflected in our history books and in the stories of Canada. Persons Day commemorates the historic decision made on that day in 1929 when the legal definition of persons was recognized as including women, but not all women.

October 18 is Persons Day in Canada https://bit.ly/3yCBg85 It falls within the month of October and 2022 marks the 30th anniversary of Women’s History Month in Canada. This commemoration provides another opportunity to seek out the stories of women who are not usually reflected in our history books and in the stories of Canada. Persons Day commemorates the historic decision made on that day in 1929 when the legal definition of persons was recognized as including women, but not all women.

The Famous Five https://bit.ly/3CPfpwP , a group of five Canadian women, challenged the definition of persons in The British North America Act which governed Canada at that time. The BNA Act used persons (plural) and he (single) and some argued that this meant women weren’t recognized as persons under the law. This argument was used to prevent women from being appointed as judges and senators. The Famous Five went to Canada’s Supreme Court to challenge the legal definition of persons. The Supreme Court decision was not in their favour, but they took the court challenge to Canada’s highest court of appeal, which at that time was the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council of Great Britain in London.

The decision in 1929 was announced by the Lord Chancellor of Great Britain: “The exclusion of women from all public offices is a relic of days more barbarous than ours. And to those who would ask why the word ‘person’ should include females, the obvious answer is, why should it not?”

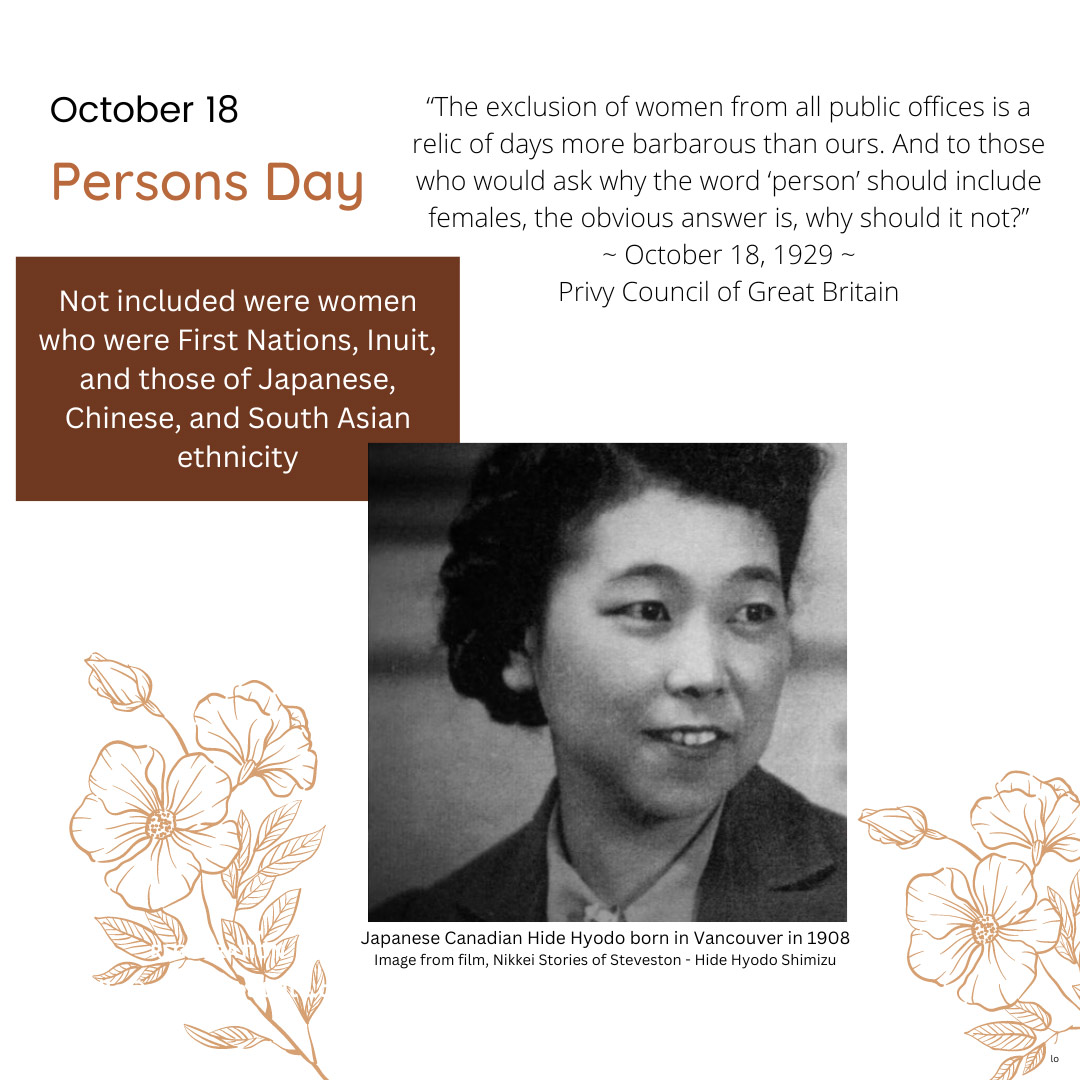

It was a victory for gender equality. However, First Nations and Inuit women and women of Asian ethnicity were not included, nor would they have access to rights such as voting until 18-33 years later.

One example is Hide Hyodo (married name: Shimizu), a Japanese Canadian woman who was born in Vancouver in 1908. She was completing a degree at the University of BC when the campus moved to Point Grey and tuition was doubled. She did not want to put her family in financial hardship, so she withdrew. She was going to look for work and then was able to attend Teacher’s Training School. She was 18 years old when she received her teaching certificate in 1926, one of the first Japanese Canadian teachers. However, she couldn’t find work as a teacher because schools refused to hire Japanese Canadians. It was one more example of the racist attitudes that prevented Japanese Canadians from finding work as a professional or tradesperson.

Hide was tenacious and she eventually found a teaching position in Steveston where she was hired to teach kindergarten to Japanese Canadian children. Hide’s skill and experience within the BC school system was a huge help when she started providing education for the Japanese Canadian children like my mom & her siblings who were held at Hastings Park http://hastingspark1942.ca in 1942, the start of internment/incarceration. Later with the Japanese Canadian Citizens League (JCCL) she and another teacher Teruko Hidaka organized the training of educated Japanese Canadians so they could teach the children in the internment/incarceration camps. The BC government had abrogated their responsibility to provide education for Japanese Canadian children.

Hide had been active with the Japanese Canadian Citizens League (JCCL) and years earlier in 1936 they selected her to be a part of a four-member delegation to appear before the Special Committee on Elections and Franchise Acts of the House of Commons in Ottawa. Japanese Canadians wanted the franchise, the right to vote, despite Prime Minister Mackenzie King’s statement that he “was not aware that either the Orientals themselves or the public generally were advocating votes for Orientals.” The Special Committee did not support the request.

Japanese Canadians would not get the franchise and the right to vote until 1949. That year, four years after the Second World War ended, the approximately 22,000 Japanese Canadians (including Hide Hyodo Shimizu) who had been forcibly uprooted, dispossessed and interned/incarcerated would be allowed to leave the camps and forced labour at farms. They had to rebuild their lives. The dispossession meant there would be no homes to return to and the ongoing racism made it difficult to move.

The right to vote was also denied to First Nations and Inuit peoples and other racialized people. Indo Canadians and Chinese Canadians would get the vote in 1947 and First Nations in 1960. Inuit received the right to vote in 1950, but they had no access to voting until 1962.

Women who were Indigenous or of Asian ethnicity faced multiple layers of discrimination including gender inequality. While there have been many steps forward, there is more to be done. Women continue to face inequities and attacks on their rights. Women of Asian ethnicity and Indigenous women still deal with issues of discrimination, greater incidents of violence, and are not represented proportionately in the higher levels of leadership in business, unions, government, and elected positions. Gender diverse people also face discrimination.

The NAJC encourages you to take one action to educate yourself and those in your networks on Persons Day and Woman’s History Month.