Highlights of June Dates in Japanese Canadian History

By Lorene Oikawa, Past President NAJC

In 2023, the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) is reviewing the highlights of dates for each month, from the period 1941 to 1949. We are looking at the actions of government and the impact on Japanese Canadians.

1942

June 10 “The first group of 70 Sandonites stepped off the train on June 10, sat on their suitcases and cried in rebellion and dismay: “Oh God, what a hole! What a hole, O God!” The Enemy That Never Was by Ken Adachi

During the peak of mining in the late 19th century, Sandon was known as the Monte Carlo of North America with 28 saloons and 29 hotels and a population of over 5,000 to 10,000. Mining declined in the early 20th century and by the time the town was designated as an internment/incarceration camp for Japanese Canadians, it was a ghost town with about 50 residents and derelict buildings. Sandon ended up being the first camp to close because of the severe winters and conditions and Japanese Canadians were moved to other locations such as New Denver.

June 16 Federal Labour Minister Humphrey Mitchell told the House of Commons that Indian Residential Schools in Williams Lake, Edmonton, St. Alberta (Alberta), and Elkhorn (Manitoba) could house up to 7,500 women and children. The federal government was separating families sending the men and boys to work on road camps and the women were left alone with the children. Two weeks later Mitchell announced the plan to use the Indian Residential Schools would not go ahead because the BC Security Commission was working on their own plans.

It wasn’t simply the government changing their mind. What is not well known is that behind the scenes, some events were happening that showed that the Japanese Canadian community is not a homogenous group of people who think the same. Not surprising, there are differences between the generations. Although most Japanese Canadians followed the orders from the government, there were some who didn’t.

Events started happening earlier in April. Etsuji Morii, well-known as a “gambling king” in the Powell Street community, had a relationship with the RCMP and was chosen by the BC Security Commission to assist with the uprooting. Morii did not represent the interests of the Japanese Canadian community and there were many stories of his authoritative actions including having Japanese Canadian men forced to report to the RCMP in the middle of the night to be sent to road camps. Opposition grew. Representatives from 38 organizations including the Japanese Camp and Mill Workers union formed the Naturalized Japanese Canadian Association also known as the Kikajin-kai. The Japanese Canadian Citizens’ League formed the Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Council (JCCC) with representatives of 53 Nisei (second generation Japanese Canadian) groups. Both groups wanted Morii to be removed. Morii lost his power, but the government rejected any other proposals.

Many of the Kikajin-kai leaders followed the government’s proposals to keep their families together by moving to what the government called self-supporting communities in Christina Lake, Bridge River-Lillooet, McGillivray Falls and Minto City or going to sugar beet farms. Considering that the government would break their promise of keeping safe the property and belongings of all Japanese Canadians and sell everything without the owners’ permission supposedly to pay for their internment/incarceration, the term self-supporting to only a few communities doesn’t seem appropriate.

The JCCC felt that Japanese Canadians needed to cooperate to gain support from the general public and the government. Members of the JCCC who disagreed formed the Nisei Mass Evacuation Group (NMEG) under the leadership of Fujikazu Tanaka and Robert Y. Shimoda. The NMEG demanded the BC Security Commission stop the breakup of their families, but they didn’t object to the uprooting.

Some Japanese Canadian men were refusing to obey the orders to go to road camps and abandon their families. By the beginning of June, women and children were still being moved to the interior to internment/incarceration camps, but about 500 men who did not report to the RCMP were still in Vancouver.

On June 2nd, the NMEG held a press conference to highlight the impasse which could be broken if the BC Security Commission would consider uprooting families instead of separating them. The press conference was suggested by Jitaro Charlie Tanaka who was an advisor to the NMEG leadership. He already had a significant role advising the Spanish consul who under the Geneva Convention was appointed to protect the human rights of Japanese aliens in Canada. He had connections with the BC Security Commission and told them to consider family uprooting and to send the married men from the road camps to prepare and build accommodations in the small towns in the interior.

In the meantime, Japanese Canadian men and boys in the road camps were hearing about the horrible conditions at Hastings Park and were worried about their families. The RCMP were at each road camp, and their presence seemed to confirm the suspicion that the Japanese Canadians were not to be trusted. Unrest was building in the camps. Some of the Japanese Canadian men started slowdowns and strikes. In mid-June 1942, three strikes halted the road camps.

BC Security Commission reps went to Ottawa to push for the reunification of families to stop the unrest, and then met with the NMEG leadership on June 30 to ask for their terms. The next day the BC Security Commission would agree to terms except for one, single men would have to stay working in the road camps. Reluctantly the NMEG agreed.

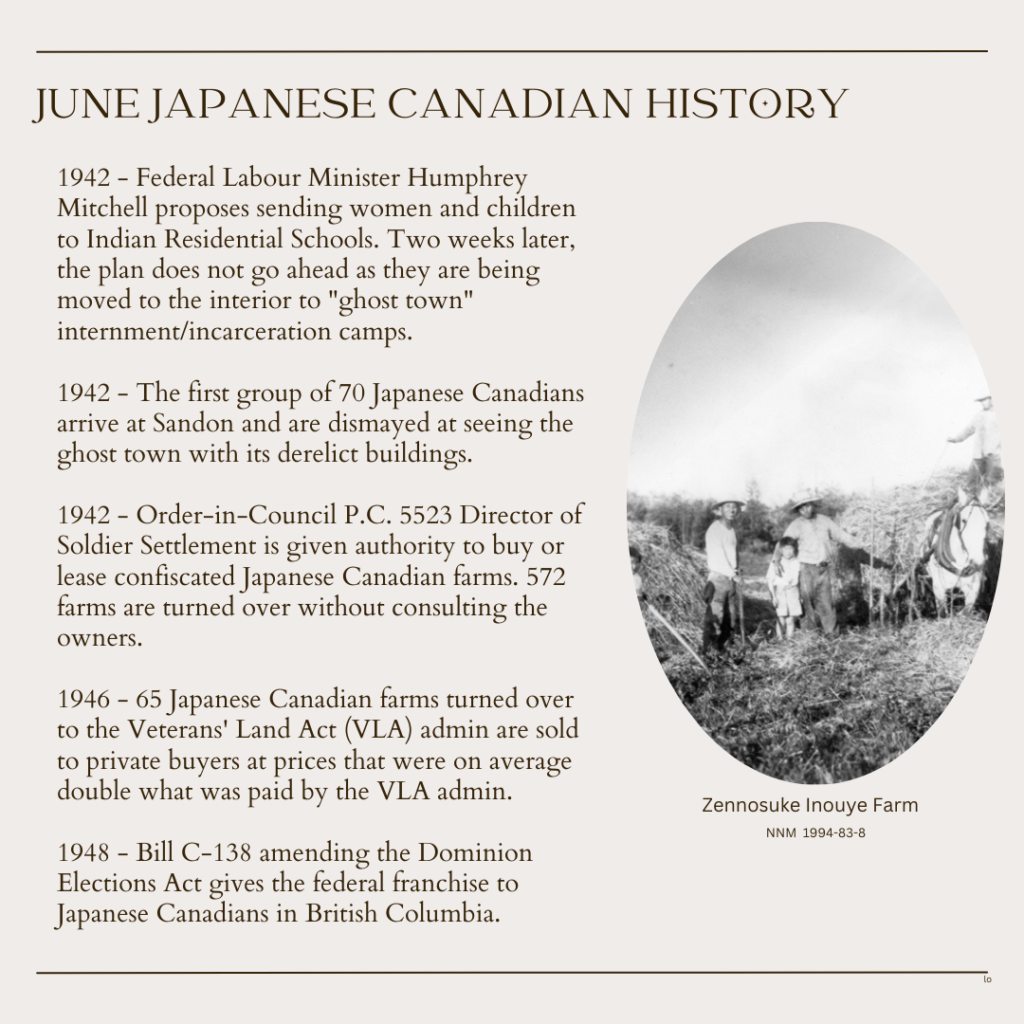

June 29 Under Order-in-Council P.C. 5523 Director of Soldier Settlement is given authority to buy or lease confiscated Japanese Canadian farms. 572 farms are turned over without consulting owners. Farms will be given to veterans of the Canadian Armed Forces. Ironic that one farm is taken from Japanese Canadian World War I veteran, Zennosuke Inouye who served Canada, but was uprooted, dispossessed, and interned/incarcerated, and exiled.

1946

In June, 65 farms that had been part of the bulk sale of Japanese Canadian property to the Veterans’ Land Act administration were sold to private buyers at prices that were on average double what was offered by the Veterans’ Land Act administration.

1948

June 15 Bill C-138 amending the Dominion Elections Act passes which gives the federal franchise to Japanese Canadians in British Columbia. However, Japanese Canadians were still not able to vote in provincial and municipal elections until 1949.