Highlights of December Dates in Japanese Canadian History

By Lorene Oikawa, Past President NAJC

In 2023, the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC) is reviewing the highlights of dates for each month, from the period 1941 to 1949. We are looking at the actions of government and the impact on Japanese Canadians.

1941

In the first week of December, the Upper Fraser Japanese Fishermen’s Association put a label on the 5,808th can of salmon which completed 3 and a quarter tons of a donation of fish to Britain from the Japanese Canadian community.

On December 7, there were about 23,149 Canadians of Japanese ethnicity. About 22,000 lived in British Columbia, which is about 2.7% of the population. Overall, Japanese Canadians represented less than a fifth of 1% of the total Canadian population. Most were Canadian citizens. Of the about 2,000 women and 3,000 men who were Japanese nationals, they had lived in Canada from 25 to 40 years.

Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service attack Pearl Harbour on December 7.

Eleven weeks later on February 26, 1942, Prime Minister Mackenzie King ordered the forced uprooting of all Canadians of Japanese ethnicity.

Hours later, at dawn December 8th, 1,200 Japanese Canadian fishing boats were taken by the Royal Canadian Navy.

On December 16, P.C. 9760 made it mandatory for all Japanese Canadians, regardless of citizenship to register with the Registrar of Enemy Aliens. Japanese Canadians had to produce their registration card on demand.

On December 17, the Pacific Coast Security League is formed. They are highly critical of Ottawa’s handling of Japanese Canadians. One of the league’s most active members is Vancouver alderman Halford Wilson who presents a motion to city council demanding the immediate removal of Japanese Canadians.

By the end of December, these racist politicians (Ian Mackenzie, A.W. Neill, Thomas Reid and Howard Green) continued their decades long campaign for the removal of all Japanese Canadians.

1942

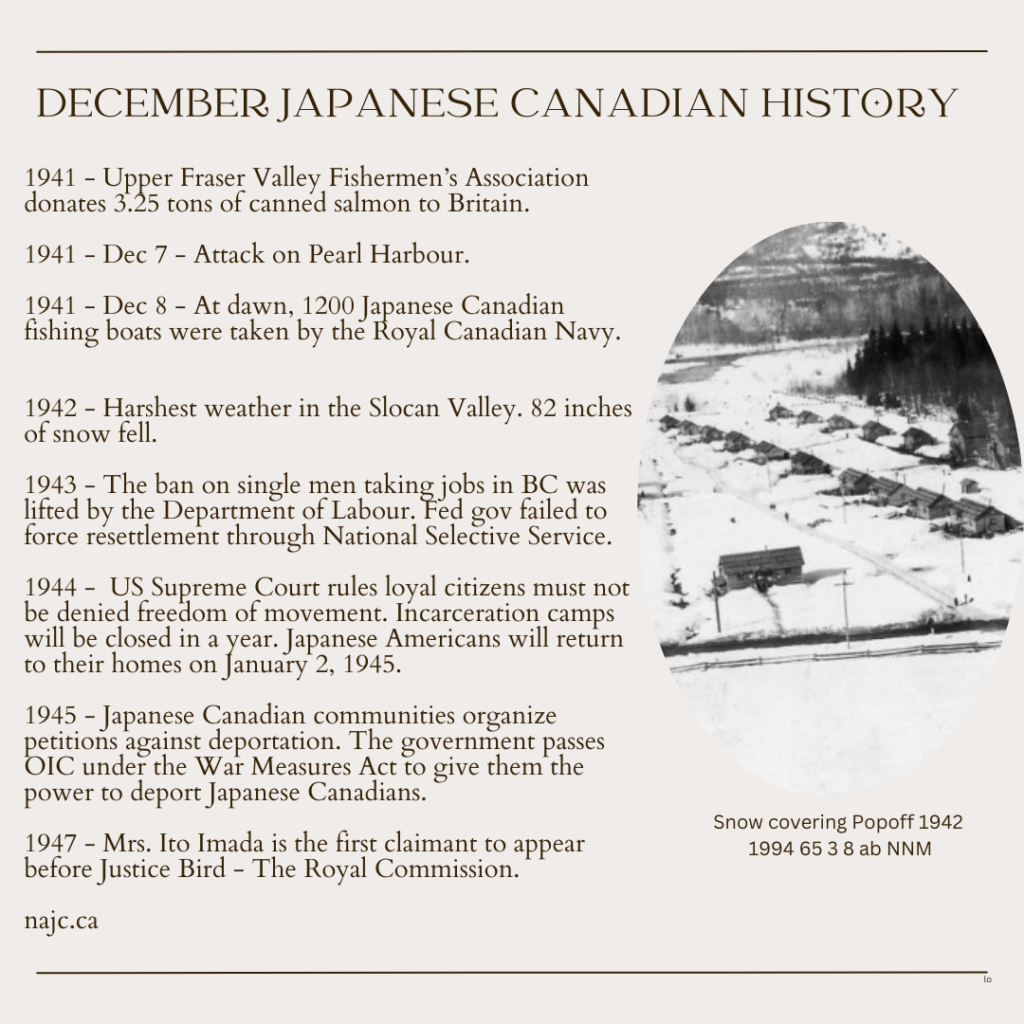

The weather in the Slocan Valley was the harshest in years. Temperatures would dip to below zero. About 82 inches of snow fell (end of October to beginning of February). For Japanese Canadians who were used to the mild temperatures on the southwest coast, it was shocking. Paths would have to be dug to get to the outhouses and to neighbours. Japanese Canadians that lived in the hastily built shacks made of green wood would wake up to find snow piled up to 5 feet against the shacks.

1943

In December, the ban on single men taking jobs in BC was lifted by the Department of Labour. The federal government failed to force resettlement through the National Selective Service (NSS) plan.

Earlier in the year the federal government decided that Japanese Canadians who were Canadian born, and naturalized citizens would be used to address the wartime labour shortages in Eastern Canada under the National Selective Service (NSS) plan. At the same time the provincial government did an about face for their prohibition of Japanese Canadians working in Crown timber lands because of the shortage of sawmill and logging workers. An announcement was made that single men would not be allowed to work in BC. Japanese Canadians held meetings and petitioned the politicians to question how they could be incarcerated and prohibited from working without regard to their citizenship and yet, now be considered citizens? Why did they have to separate from their families to go east when there were labour shortages in BC? Less than 40 were persuaded to go east. The following year, the federal government removed the compulsory aspect of NSS and job offers were posted in the camps. To assist with resettlement, the Department of Labour would set up offices in Winnipeg, Fort William, Toronto, and Montreal.

Complaints about the conditions of the incarceration/internment camps have been made to Ottawa, the International Red Cross and the Spanish consulate. On December 21, 1943, Labour Minister Mitchell announced the appointment of a Royal Commission to investigate. It was noted that Mitchell commented that his department had received complaints that provisions were “too generous.” An attempt to deflect. Also, he instructed the Royal Commission to consider that the camps were temporary relocations and not permanent centres.

Some may wonder, why is the Spanish consulate involved? Issei (first generation settlers) were under the protective power of the Spanish government. Issei were exempt from the NSS because they were not Canadian born or legally able to obtain citizenship through the naturalization process.

Japanese Canadians would not have experienced less racism in eastern Canada. 54% of Canadians supported “sending back” all Japanese Canadians to Japan as reported in a Gallup Poll published in December 1943. The fear mongering and stereotypes reinforced by racist politicians and others contributed to the persistent discrimination and hostility. Japanese Canadians were seen as the enemy not as citizens.

1944

In the USA, a decision was made on December 17, 1944 to rescind their exclusion orders and close all incarceration camps within a year. Japanese Americans could return to their homes as of January 2, 1945.This decision was made after their Supreme Court had made a ruling in that the War Relocation Authority (American version of the British Columbia Security Commission) did not have any authority to hold citizens “who are concededly loyal.” Mitsue Endo, a former state employee of California, had her case brought forward by James Purcell, a civil rights lawyer. The ruling meant that Mitsue and other Japanese Americans could not be denied freedom of movement.

The Canadian government did not want Japanese Canadians to have freedom of movement, so they continued to push for the deportation of Japanese Canadians.

Since 1940, the police had been monitoring Japanese Canadians and reported that they were “law-abiding” citizens. Military leaders also informed the government that no action was needed. In August, under questioning by the CCF (Co-operative Commonwealth Federation, the precursor to the New Democratic Party) Prime Minister King admitted there had been no acts of sabotage or disloyalty exhibited by any Japanese Canadian.

Japanese Canadians would not be released until 1949, four years after the Second World War ended.

1945

Japanese Canadian committees organized petitions against deportation across Canada. The Slocan District Committee organized a petition signed by 2,010 Japanese Canadians who did not want to be deported to Japan. They sent it to Prime Minister King. By coincidence, the petition was received in Ottawa on the same day, December 15, 1945, when an Order-in-Council was passed under the War Measures Act giving the government the power to deport Japanese Canadians.

1946

Legal challenges against deportation continued.

On December 2, 1946, a ruling by Privy Council was handed down, deportation orders were valid because the Canadian government had the authority to do what it wanted under the War Measures Act. It was over nine months since the unfavourable ruling by the Supreme Court. The court action had forced Cabinet to suspend deportation. Cabinet considered their next step. 4,000 Japanese Canadians had been sent to Japan. They would have to change deportation to the categories approved by the Supreme Court if they were to continue. By the following month, Prime Minister King repealed the deportation orders.

1947

December 8, 1947. The first claimant to appear before Justice Bird was Mrs. Ito Imada who claimed her Fraser Valley farm was sold for a loss. The Royal Commission was set up in July and was limited to looking at losses from the sale of properties in the care of the Custodian of Enemy Property if they “failed to exercise reasonable care.”

Each claimant underwent rigorous questioning. Justice Bird and government counsel pushed for details about the property including the circumstances. Even with providing all information, not all applicants received compensation. Not all claims were considered, and only monetary losses were considered.

Main sources:

The Enemy That Never Was by Ken Adachi

The Politics of Racism: The Uprooting of Japanese Canadians During the Second World War by Ann Gomer Sunahara