by David Fujino

I was raised Canadian like the other kids in my neighbourhood. At the same time, my mom always told me about the Internment, and Greenwood, where I was born, so I knew I was a Japanese Canadian, but it didn’t seem a big deal — it was just another thing to take in as a growing child. I mean, what do you really understand, anyway, as a pre-schooler?

I can tell you that before settling in Toronto, we lived for brief periods in Oakville, then Hamilton. A wealthy gentleman farmer, Mr. Parker of Oakville, sponsored my parents, me, and my older brother, Donald Sakai, to relocate out east and work on his 100 acre estate. Then in Hamilton, we stayed briefly with relatives where I remember (perhaps inaccurately?) watching from my bedroom window as an endless array of filled Coke bottles passed by on conveyor belts.

As soon as we landed in downtown Toronto (St. Patrick St. near Queen), I remember being invited by the Sakai brothers to see a large live fish sloshing around in a zinc basin full of water on the kitchen floor. My mom said the brothers were from Steveston and many of them were interned with us in Greenwood. It was a cause for celebration. The brothers smiled and proudly showed me the fish. In the following days, I’d occasionally satisfy my curiosity and take a bite of the maguro sashimi my big brother was happily dipping in shoyu.

But as I grew older and started junior kindergarden, I was exposed to society and other kids and quickly learned to lie, and I soon became aware of difference — I became self-conscious. Race. I looked different and so did my family. But like most kids, I had some fitting in to do, so I took refuge in the class gang and broadly taunted other kids with cries of “You dirty DP.” Mom explained that D.P. was shorthand for Displaced Persons — the Jews, Ukrainians, Poles, Germans, Lithuanians and the many Europeans fleeing persecution, death, and war. And while mom never lectured anyone, she firmly told me it wasn’t something I should say. After all, we’d been called “Japs” and many other demeaning things, and it was wrong to stoop to that level and hurt others. They’re people, too.

It was a scruffy time, and I was vaguely aware that we, too, were displaced persons in Canada, the country of my birth. I was also aware that my closest friend across the street, Carl Lombardo, was Ukrainian and Italian, and his mother, Olga, was a good friend of my mom’s. They were friends. Decent people. But that was the start of my feeling inescapably different.

A year or so later, we moved from St. Patrick to Crawford Street and I was again the new kid on the block. It seems I exhibited a facility with speaking and reading and I was asked to take part in reading passages from the Bible at Sunday church services. It may seem odd, but I wasn’t so interested in learning about church doctrine or the meaning of The Holy Trinity; no, I instinctively felt I could read in front of a congregation and be good at it. (Perhaps these early impulses were part of my wanting to be an actor, many many decades later.)

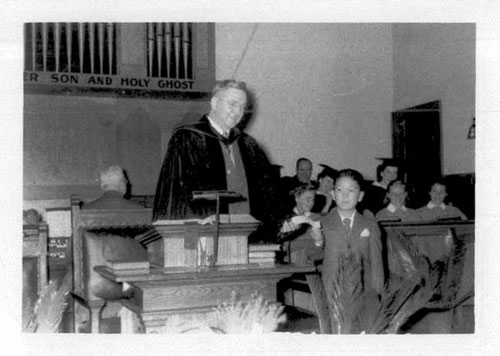

I still have the b&w photo at home. Dressed in his Sunday best, a little “Oriental” boy warily accepts a white envelope from the beaming and benign Reverend Wade [spelling?] at the Crawford Street Congregational Church. My mom had carefully explained that the Reverend asked if I would attend the Sunday service and pose for a photograph as a Korean refugee. The church was sending money to assist the Korean people (if memory serves) and they wanted to make the occasion a “photo op”, as we say today. My mom said it ‘was a little odd’, and I didn’t have to do it. It was my choice. I was about 8 or 9 years old at the time.

Last time I checked, the church building still stands on Crawford Street, but the little “Oriental boy” in the photo no longer exists. Shortly thereafter, I stopped going to church. I have no interest in ever going back.

What strikes me is that these tales actually have to do with someone else’s past. They belong to the Nisei experience. By this I mean that the Reverend’s request to have me fulfill his publicity requirements by standing in for another Asian community probably wouldn’t be tolerated or given the time of day in today’s climate. Probably. But back in the good old days, it was routinely accepted as something the hakujin want, so a number of Nisei — and this includes my open-thinking mom — would have felt compelled to at least entertain such an odd and ultimately compromising request. (Note: Because all of the persons mentioned in this article have long since passed away, I freely use their actual names and refer to actual incidents.)

In my late high school and early university years, the afore-mentioned Mr. Parker re-entered our lives. He’d already shown good faith. He attended Don’s wedding and had gifted him with a doctor’s bag at his graduation ceremony at the Faculty of Medicine at U of T. Roughly around this time, my mother fell upon hard times. She’d become a struggling single mom and she asked Mr. Parker if he could help her out — which he did — and I do thank him for that.

However, on one occasion Mr. Parker observed that mom should tell me — her “lazy son” — to help out more with household chores such as taking out the garbage and mowing the lawn. At the risk of making myself look bad and overly pampered, let me report that Mom said I didn’t have to do any of those things! She explained that I had no real relationship with Mr. Parker, but she and Don did, and I was not obliged to follow Mr. Parker — an interesting point of distinction which remains with me today.

Very often, the relationship of the Nisei to certain hakujin has made me think of the ‘freed’ African-American slaves. You’ll recall that, as mandated by our Federal government, JCs got released from the internment camps, but only if they were “sponsored” by hakujin out east. Again, slaves follow the masters’ orders.

And somehow, to this day, I don’t feel entirely free. After all these years.