JAPANESE CANADIAN HISTORY

Early History

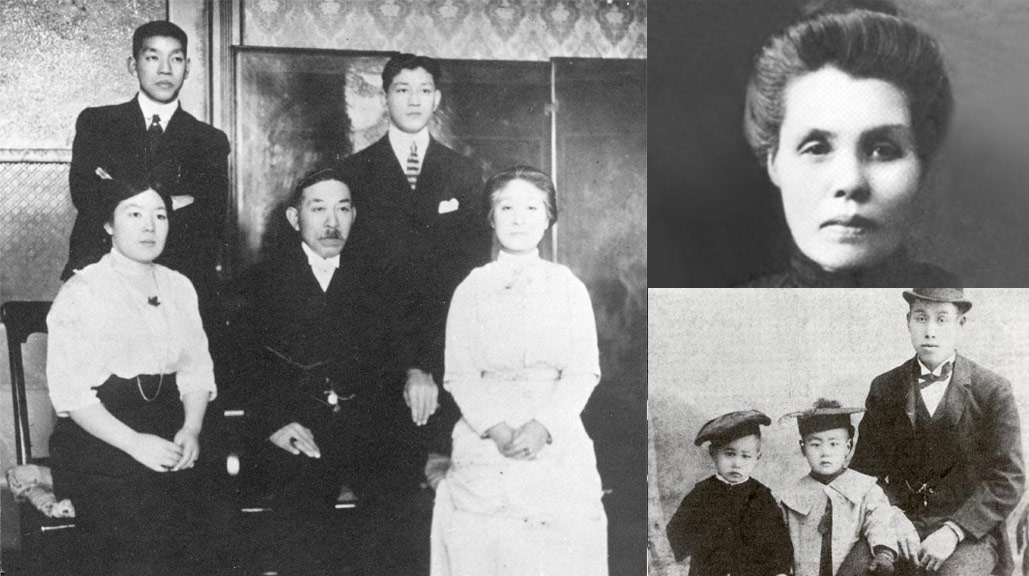

During the Meiji era Japanese society became more liberal, allowing young Japanese to venture to other countries. The first known Japanese to settle in Canada was Manzo Nagano in 1877, although there were reported cases of Japanese fishermen shipwrecked along the coast of British Columbia prior to that date.

Waves of immigrants followed, young men in particular, to seek adventure, wealth and, in some cases, independence from family obligations. By 1901 nearly 5000 Japanese were living in Canada.

Through the exchange of photographs and letters, single men arranged for brides from Japan. These “picture brides” began arriving in 1908 and at their peak in 1913 some 300 to 400 came to Canada. As early as 1885 the Canadian government attempted to discourage Chinese immigration by applying a Head Tax, but such restrictions did not apply to the Japanese. Between 1905 and 1907, Canada saw the largest influx of immigrants. By 1907 the Japanese population rose to over 18,000.

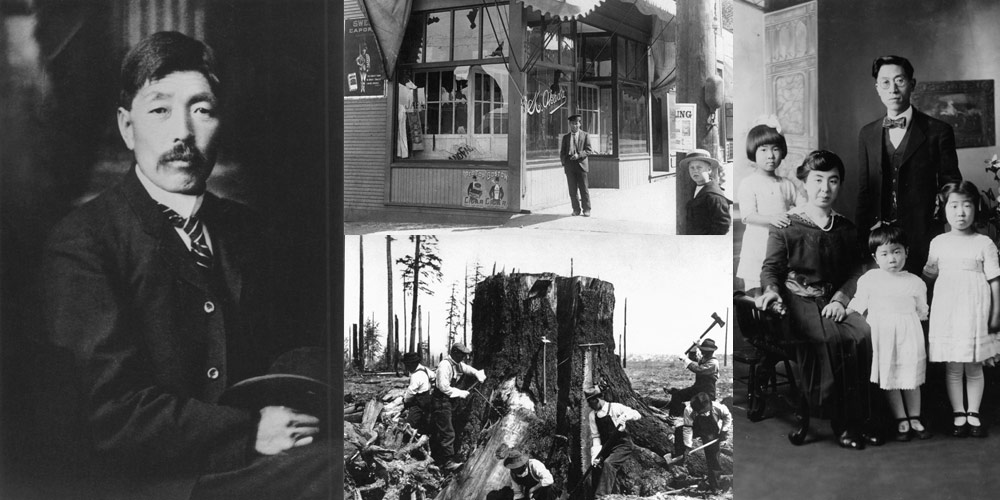

Most immigrants were farmers and fishermen; some were business people. Only a few were well educated and from the aristocratic class. Denial of the franchise prevented Japanese Canadians from the right to vote, from participating in professions, and holding public office.

In 1900, Tomekichi Homma, a naturalized Canadian citizen, applied to have his name placed on the voter’s list. His request was denied and so he appealed to the courts.Unable to enter the professions, most found employment in logging and lumbering, mining and fishing, while others started businesses. Anti-Asian sentiment grew within the white community, and on September 7, 1907 a large angry mob marched on Chinatown shattering windows, breaking into stores and frightening the residents. The mob then moved towards Powell Street, the home of the Japanese community. Pre-warned, the Japanese were ready for the onslaught and fought back, forcing the crowd to retreat. However, the stores and businesses were heavily damaged. This hostility towards Asians was an indication of the racism that the Japanese would face throughout the early period of history in Canada.To discourage Asians from settling and remaining in BC, the government passed laws discriminating against non-whites. In 1908, with agreement from Japan, the government of Canada limited the number of male immigrants to 400 per year. No limits applied to women and children.

In 1931 Japanese Canadian veterans who fought for Canada in World War I received the right to vote. They were the only Japanese Canadians allowed to vote.

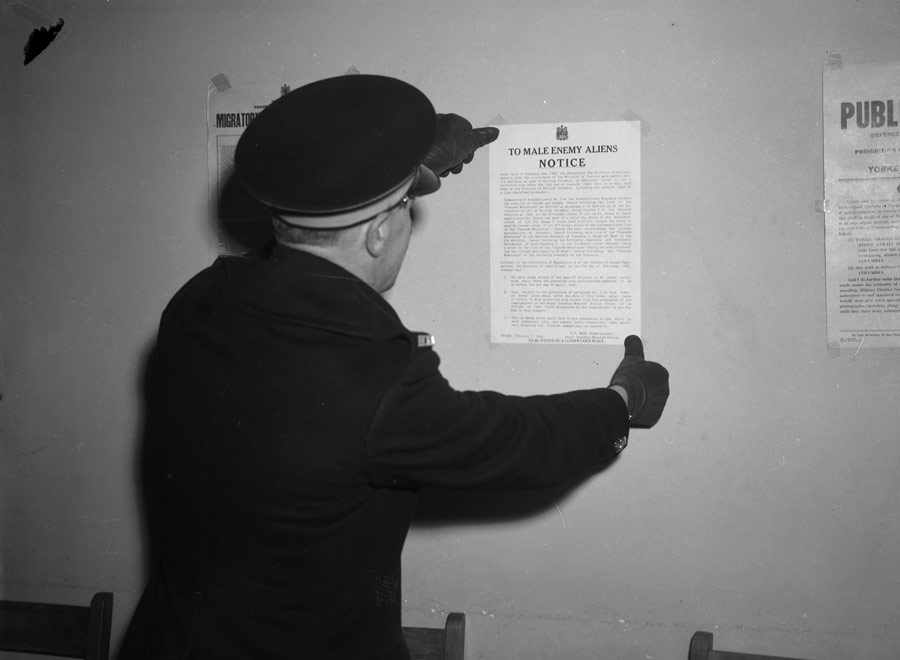

On January 8, 1942 the Asia-Pacific war was seen as an opportunity to get rid of the “Japanese Problem”. The Canadian Government invoked the War Measures Act, stripping Japanese Canadians of their civil rights and giving the government unlimited powers that could not be challenged in court. They were labelled as “enemy aliens” and dealt with as “persons of Japanese racial origin”.

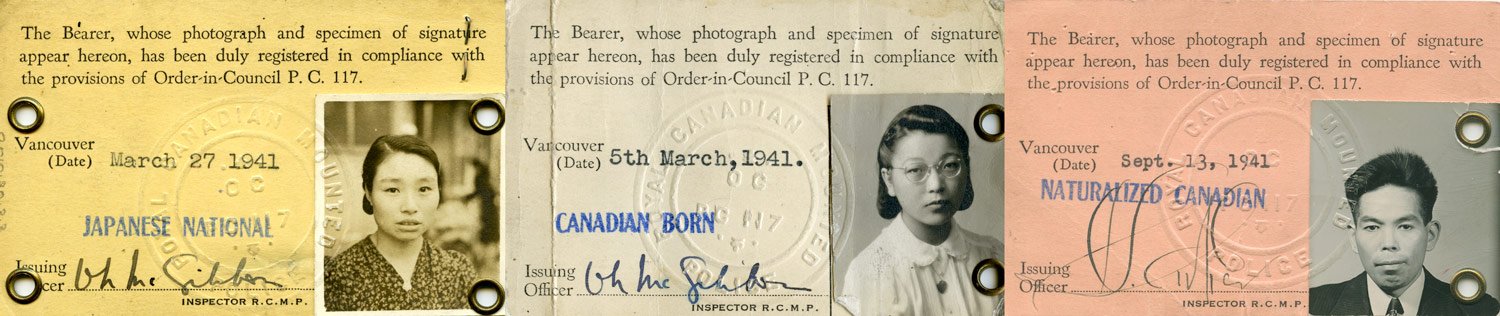

Successions of Orders-in-Council were passed to further strip them of their rights. Six months before Japan attacked Pearl Harbour, Japanese Canadians over the age of 18 years were fingerprinted and registered with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police. All Japanese Canadians were forced to carry an identification card until 1949.

WWII Experience – Internment and Dispersal

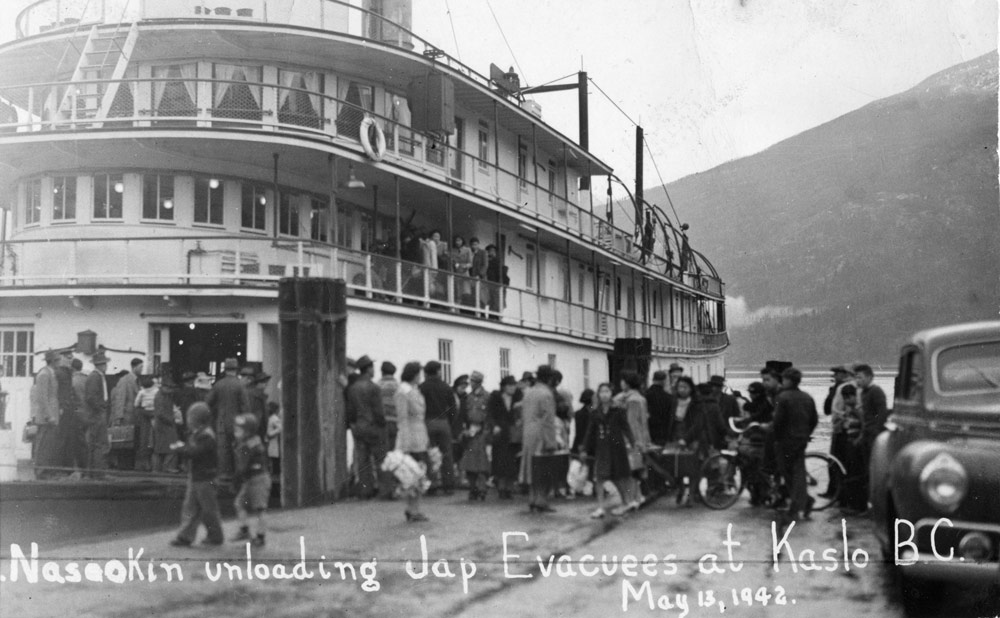

On February 7, 1942, the government passed Order-in-Council 365 that created an area 100 miles (160 km.) inland from the coast as a “protected area”. The BC Security Commission, a federal government agency, was empowered to systematically carry out the expulsion of “all persons of Japanese racial origin” from this restricted area. Some from along the coastline were sent to Hasting Park livestock building in Vancouver.

Families were separated, men were sent to road camps or prisoner-of-war camps in Ontario. Some remained as a family and were sent to Manitoba (and Alberta) to work on the sugar beet farms where they faced meagre income for back breaking labour, inadequate housing, and cold winter months.

Internment centres were created in the interior of B.C. where they lived in multiple family units that were hastily built shacks, tents, abandoned mining towns, and unused buildings. Living under these conditions, the internees suffered unimaginable hardships.

Properties left behind were to be held in trust but Order-in-Council 469 passed on January 19, 1943 authorized the government to sell the properties without the owners’ consent. A loyalty survey carried out by the RCMP on March 12, 1945 guaranteed the expulsion of all Japanese Canadians from the province of BC. The ultimatum: move east of the Rocky Mountains or be exiled to Japan. Restrictions were kept in place for four years more years and Japanese Canadians were not allowed to return to the west coast until April 1, 1949. They received the right to vote in June 1948 federally and on March 31, 1949 in BC.

Renewal – The Centennial and Redress

In 1977, the Japanese Canadian community commemorated the 100-year anniversary of the first Japanese immigrant to settle in Canada. Celebration events were held across the country as the community came to terms with its history, including the wartime experience.

The National Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association was formed in 1947 to represent the welfare of the Japanese community. In 1980, with the name changed to National Association of Japanese Canadians, a movement for redress became a community project. With courage and determination our leaders persevered, overcoming innumerable obstacles.

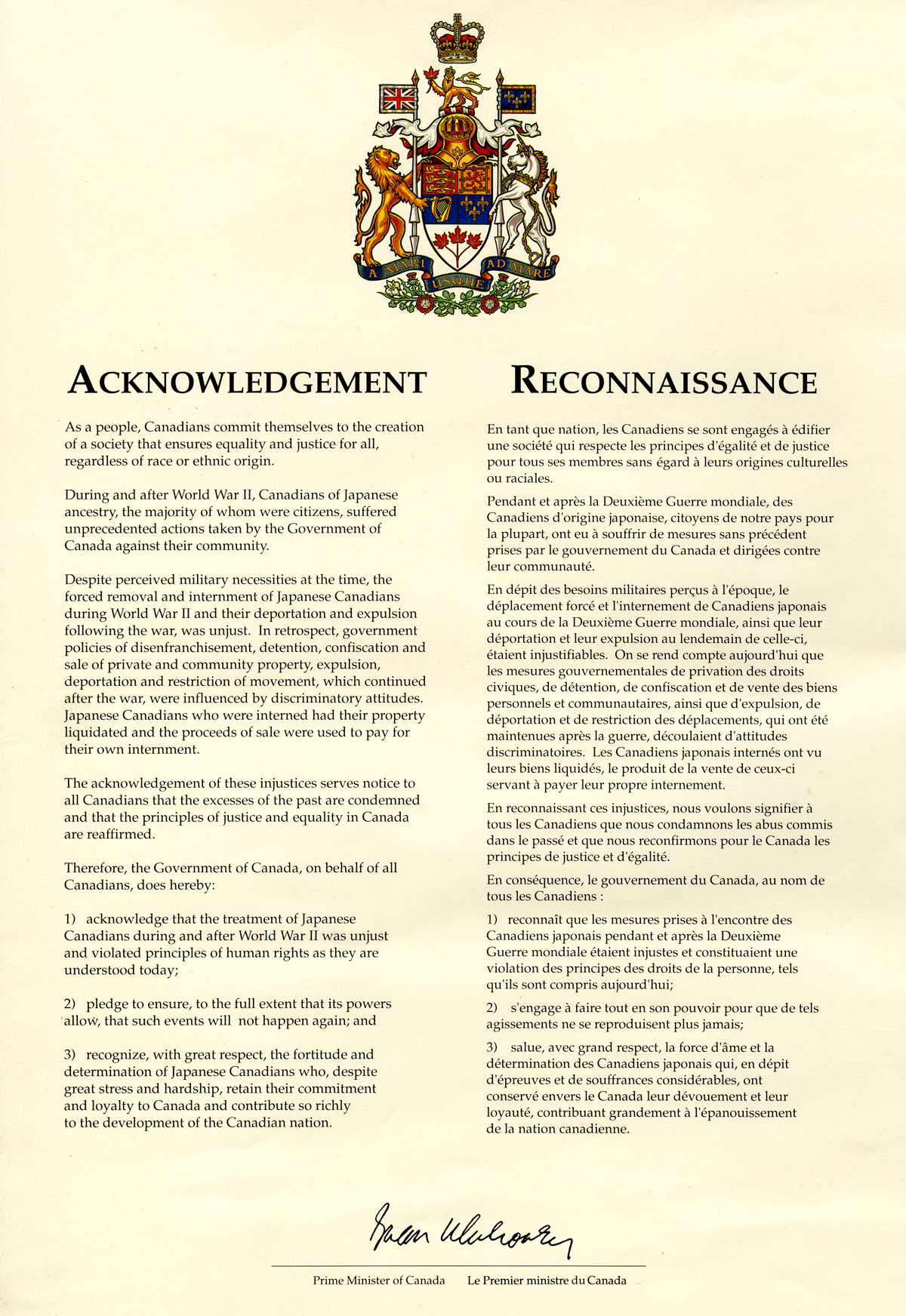

On September 22, 1988 the Redress Agreement was signed by Art Miki, President of the National Association of Japanese Canadians and Prime Minister Brian Mulroney. The Prime Minister acknowledged the injustices suffered by Japanese Canadians. He characterized the treatment of Japanese Canadians as morally and legally unjustified, and called upon Canadians as a nation to face up to the historical facts of the incarceration , property seizure, and disenfranchisement, and pledged that such injustices would never again be countenanced or repeated in Canada. (House of Commons, Debates, September 1988, page 19499)

Japanese Canadians Today

The redress settlement included symbolic individual compensation to those who were affected, and a Community Fund to help revitalize the community. Cultural Centres were built across the country and many projects were funded by the Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation in the 10 years following Redress.

Despite the revitalization of the community, the forced dispersal policy left the community with a high intermarriage rate that affected community growth in Canada. A provision was also included to establish the Canadian Race Relations Foundation. The Redress achievement gave Japanese Canadians courage to talk about their experiences and to regain pride in their heritage.

Video – UBC Students

Japanese Canadian Timeline

1833 – 2000

1833

First recorded instance of Japanese shipwrecks off the west coast of what would become British Columbia. Two survivors of a wreck off the Queen Charlotte Islands are taken by the Hudson’s Bay Company to England. Over the next several decades, there are repeated shipwrecks. Some sailors manage to return to Japan where they might face prosecution by the Tokugawa government, which prohibits travel to foreign countries. Others are reported to have settled in aboriginal communities along the British Columbia coast.

1873

Two Canadian priests travel to Japan to do missionary work. Interestingly, these missionaries became involved in founding several schools in Japan and contributed to the modernization of the Japanese education system.

Arrival

1877

Manzo Nagano lands in New Westminster, the first Japanese person known to land and settle in Canada.

1887

Gihei Kuno, a fisherman from Mio-mura in Wakayama-ken, visits Canada and returns to recruit fellow villagers to settle in the village of Steveston at the mouth of the Fraser River. Steveston becomes the second largest Japanese-Canadian settlement before World War II. Mio, also known as America-mura becomes one of the largest single sources of Japanese emigrants to Canada.

Official emigration to Canada commences with the opening of a regular steamship service between Yokohama and Canada.

Yo Shishido becomes the first Issei woman to settle in Canada, where she takes up residence with her husband, Washiji Oya, a store proprietor on Powell Street.

1889

The first Nisei, Katsuji, is born to Yo and Washiji Oya.

The first Japanese consulate opens in Vancouver.

1893

Yoichi Tanabe apprentices with a Chinese tailor in Vancouver. He goes on to open the first Japanese Canadian tailor shop in Canada.

White and First Nations fishermen stage a strike, demanding a reduction in number of fishing licenses issued to Japanese.

1895

British Columbia Government denies franchise (voting rights) to citizens of Asiatic origin

1896

Rev. Goro Kaburagi becomes the first ordained minister of the Japanese Methodist church. He establishes a Japanese language weekly, the Bankuba Shuho.

1897

The Japanese Fishermen’s Association is organized in Steveston, BC, with Tomekichi Homma as President.

1898

Tokutaro Chikamura and Tsukichi Kato purchase 230 Powell Street, becoming the first Japanese immigrants to own property on Powell Street

1900

Tomekichi Homma, a Vancouver boarding house keeper and naturalized Canadian citizen, applies to be included on the voters’ list. After refusal by the Collector of Voters, a British Columbia judge declares ultra vires a clause barring Asians from voting, but this decision is later overturned by the Privy Council of Britain in 1902.

1904

Isaburo Kishida, a professional gardener from Yokohama, designs and landscapes Victoria’s Japanese Tea Gardens, which quickly become very popular. He is then commissioned to plan a Japanese rock garden, which is eventually incorporated into the world famous Butchart Gardens.

1905

The first Buddhist temple in Canada opens at the Ishikawa Hotel on Powell Street, Vancouver.

1906

July The first Japanese language school, the Vancouver Kyoritsu Nippon Kokumin Gakko, is established at 439 Alexander Street. A second brick building soon joins the original wooden structure. In 1920 the name is changed to the Vancouver Japanese Language School.

At Lord Strathcona School in Vancouver, Japanese Canadian students are enrolled in a public school alongside white students for the first time.

Kumataro Inamasu is the first documented Nikkei living in southern Alberta.

More than 9,000 Japanese immigrants enter Canada from 1906-08.

1907

September 9 A mob of white supremacists gathers in Vancouver and inflicts severe damage to Japanese and Chinese immigrant quarters. Powell Street receives extensive damage. The riot is immediately followed by a general strike of Vancouver’s Asian workers.

1908

The Hayashi-Lemieux “Gentlemen’s Agreement” restricts further Japanese immigration to 400 male immigrants and domestic servants per year, plus returning immigrants and their immediate family members.

The shasshin kekkon, “picture bride” system of marriage becomes widespread.

1909

A directory of Japanese immigrant businesses shows 568 businesses in the Powell Street area.

1910

March 5 A snow slide at Roger’s Pass buries 62 men. 32 issei are among the dead—the single biggest loss of life in Japanese Canadian history. Families of the victims receive $220 each.

Baseball is very popular among Japanese Canadians. The first game between teams from two communities features the Victoria Nippons vs. the Vancouver Nippons.

1912

The Asahi baseball team is formed. The team quickly becomes famous for its sacrificing, base-stealing and fielding. They become the most popular team in the Lower Mainland with a legion of non-Nikkei fans.

1916

Chitose Uchida becomes the first Nisei to graduate from a Canadian university qualified as a schoolteacher. She is unable to find employment, except teaching English in the Nikkei community.

We Went to War

1916-1917

Hoping to prove their loyalty to Canada, over 200 Nikkei volunteers attempt to enlist in the Canadian Army. After being rejected in British Columbia, 195 issei volunteers, and one nisei—Private George Uyehara—travel to Alberta to join Canadian battalions of the British army and are shipped to Europe. 54 are killed and 92 wounded.

1918-1919

The Canada-wide influenza epidemic claims over 100 Japanese Canadians.

1919

Japanese fishermen control nearly half of the fishing licenses (3,267). Department of Fisheries reduces number of licenses issued to “other than white residents, British subjects and Canadian Indians”. By 1925 close to 1,000 licenses have been stripped from Japanese Canadians.

1920

Japanese Canadian mill workers under Etsu Suzuki form the Japanese Labour Union, the first Japanese-Canadian union.

April 9 The Japanese Canadian War Memorial cenotaph is officially unveiled in Stanley Park near Lumberman’s Arch on the third anniversary of the Battle of Vimy Ridge. Sitting atop the sandstone column is a marble lantern containing an eternal flame. Says Sergeant Yasuzo Shoji, veteran of the 52nd Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, “We don’t forget what we owe to Canada and we were proud to fight when Britain declared war on the common enemy.”

1922

Lord Byng annex in Steveston, a school attended by both Japanese and non-Japanese students, becomes the first and only school in BC to hire a Japanese Canadian teacher. However the teacher, Hide Hyodo, is only permitted to teach the Japanese Canadian students.

1924

The labour union newspaper Minshu (The Daily People) begins publication under the leadership of Etsu Suzuki.

1926

The Asahi baseball team wins the Terminal League Championship—the first of several league championships over the next 15 years.

1929

Jun Kisawa, an Issei fisherman, wins a court battle to overturn restrictions against Japanese Canadians using motorized fishing boats.

1930

June Shige Yoshida, of Chemainus on Vancouver Island, forms the first Japanese Canadian boy scout troop in the British Empire. Barred from joining a local troop five years earlier, he studied on his own by correspondence, earning the highest possible rank and a warrant from the Boy Scouts of America granting him the right to form his own troop.

1931

World War I Issei veterans receive the franchise, and become the only Japanese Canadians qualified to vote.

1936

The Japanese Canadian Citizens League—the first citizens’ association—is founded, and sends a delegation of Nisei citizens to Ottawa to plead unsuccessfully for the franchise.

1937

March to August Compulsory registration of all Japanese Canadians over 16 years is carried out by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

Shuichi Kusaka graduates from the University of British Columbia. He goes on to work under Albert Einstein at Princeton University.

To mark Victoria’s 75th Anniversary, the Japanese Canadian community donates hundreds of ornamental cherry trees. The trees continue to bloom to this day.

1938

November 24 The New Canadian is established as the first English-language Nikkei newspaper with its motto, “The Voice of the Second Generation”. The first editor is Shinobu Peter Higashi but he is soon replaced by Tom Shoyama. Various nisei including Irene Uchida, Muriel Kitagawa, and Toyo Takata passed through The New Canadian at one point or another.

The first Canadian-born Buddhist Minister, Takashi Tsuji of Mission, BC, is ordained. He eventually leaves for the States, where he is elected Bishop of the Buddhist Churches of America.

Expulsion

1941

January 7 In a split decision, a Special Committee of the Cabinet War Committee recommends that Japanese Canadians not be allowed to volunteer for the armed services on the grounds that there is strong public opinion against them.

March to August Compulsory registration of all Japanese Canadians over 16 years is carried out by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police.

December 7 Japan attacks Pearl Harbor. Canada declares war on Japan. Under the War Measures Act, Order-in-Council P.C. 9591 requires all Japanese nationals and those naturalized after 1922 to register by February 7 with the Registrar of Enemy Aliens.

December 8 Canada declares war on Japan. 1200 Japanese fishing boats rounded up by the Canadian Navy. Japanese language schools close. Insurance policies are cancelled. All three Japanese-language newspapers closed down by R.C.M.P. The New Canadian becomes the sole paper allowed to publish. It turns into a bilingual publication and is the main source of community news, and government policy directives.

December 16 Order-in-Council P.C. 9760 requires all persons of Japanese origin, regardless of citizenship, to register.

The light atop the Japanese Canadian War Memorial in Stanley Park is extinguished.

Of the 23,303 persons of Japanese origin in Canada, 75.5% are Canadian citizens (60.2% Canadian-born and 14.6% naturalized citizens).

1942

January 16 Order-in-Council P.C. 365 creates a 100-mile ‘protected area’ on the coast of British Columbia from which male enemy aliens are excluded.

February 7 All male Japanese Canadian citizens between the ages of 18 and 45 are ordered to be removed from a 100-mile-wide zone along the coast of British Columbia.

February 24 Order-in-Council P.C. 1486 empowers the Minister of Justice to control the movements of all persons of Japanese origin in the protected area.

February 26 Mass evacuation of Japanese Canadians begins. Some are given only 24 hours notice. Cars, cameras and radios areconfiscated for “protective measures”. A curfew is imposed.

March 4 Under Order-in-Council P.C. 1665 Japanese Canadians are ordered to turn over property and belongings to the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property as a “protective measure only”.

March 16 First arrivals at Vancouver’s Hastings Park pooling centre. All Japanese Canadian mail is censored from this date.

March 25 British Columbia Security Commission initiates a scheme of forcing men to road camps and women and children to “ghost town” detention camps.

April 26 First arrivals in Greenwood. Greenwood is the first "ghost town" internment camp in the interior of BC.

May 21 1,021 men prepare the five "ghost towns" of Greenwood, Kaslo, New Denver, Slocan City and Sandon for habitation as uprooted Japanese Canadians were arriving.

June 29 Under Order-in-Council P.C. 5523 Director of Soldier Settlement is given authority to buy or lease confiscated Japanese Canadian farms. 572 farms are turned over without consulting owners.

November 30 First Kaslo issue of The New Canadian is published. The newspaper and its staff are moved to the “ghost town” on Kootenay Lake in late October. The New Canadian becomes the primary source of information between the various camps and across the country and is used by the government to disseminate information.

By the end of the year, approximately 12,029 persons are in detention camps in the interior of British Columbia, 945 men are in enforced labour camps, 3,991 are placed as labourers on sugar beet farms in the Prairie provinces, 1,161 are in voluntary self-supporting sites outside the ‘protected area’, 1,359 are given special work permits, 699 are interned in prisoner-of-war camps in Ontario, 42 are repatriated to Japan, 111 are in detention in Vancouver and 105 are in hospital in Hastings Park, approximately 2,000 were living outside the ‘protected area’ and allowed to remain in place but required to register and give up prohibited items, and subject to restriction of activities.

1943

January 19 Order-in-Council P.C. 469 allows the government, through the Custodian of Enemy Alien Property, to sell Japanese-Canadian property held in custody without owners’ consent.

People are gradually released from camps if they agree to move east of the Rocky Mountains. They encounter severe hostility from the public. Many cities, among them the City of Toronto, are closed to persons of Japanese ancestry.

The Japanese Canadian Committee for Democracy and the Co-Operative Committee on Japanese Canadians (a white, mainly Christian group) are organized to assist in re-settlement.

1944

August The Government announces a program to disperse Japanese Canadians throughout the country, to separate those who are “loyal” from those who are “disloyal”, and to “repatriate” the disloyal to Japan.

1945

January At the request of the British government, Japanese Canadians are allowed to enlist.

Those remaining in the camps are canvassed for “loyalty”, and told to choose between “repatriation” to Japan and immediate movement east of the Rocky Mountains. Some 10,632 people, facing uncertainty and unable to confirm new residences east of the Rockies, sign repatriation forms. Nearly half later apply to rescind their signatures.

Orders-in-Council P.C. 7335, 7356 and 7357 empower the government to assess the loyalty of Japanese Canadians, order their deportation and strip them of citizenship.

January-May 150 Japanese Canadians volunteer for service with the Canadian army in the Far East.

April 13 Beginning of intimidation campaign towards Japanese Canadians living in British Columbia to move to Eastern Canada or be deported to Japan.

September 2 Japan surrenders after atomic bombs are dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The New Canadian moves to Winnipeg, in line with its own editorial policy advocating Eastern relocation. Editor Tom Shoyama volunteers for the Canadian Army and Kasey Oyama takes over the editorship. The Kaslo era ends, after just two and a half years.

1946

January 1 On expiry of the measures under the War Measures Act, the National Emergency Transitional Powers Act is used to keep the measures against Japanese Canadians in place.

May 31 “Repatriation” begins; 3,964 go to Japan, many of whom are Canadian citizens.

December The Privy Council upholds a Supreme Court decision that the deportation orders are legal. By this time more than 4,000 people have been deported to Japan.

1947

January 24 Federal cabinet order-in-council on deportation of Japanese Canadians repealed after protests by churches, academics, journalists and politicians.

April The Citizenship Act extends the franchise to Canadians of Chinese and South Asian origin, but excludes Japanese Canadians and aboriginal peoples.

July 18 A commission is set up under Justice Henry Bird to examine the losses sustained by Japanese Canadians, who receive compensation cheques totalling $1.2 million, a small fraction of the value of their property.

September The National Japanese Canadian Citizens Association is established at a conference in Toronto.

1948

June 15 Bill 198 amends the Dominion Elections Act to remove the clause denying the franchise to Japanese Canadians.

The New Canadian moves to its final home in Toronto and Kasey Oyama is soon succeeded as editor by Toyo Takata.

The Post War Years

1949

March 31 Removal of last restrictions; restrictions imposed under the War Measures Act are lifted, and Japanese Canadians gain full rights of citizenship and are free to move anywhere in Canada.

1950

Order-in-Council P.C. 4364 revokes an order prohibiting immigration of “enemy aliens”, and provides for some of those deported to re-immigrate to Canada. Eventually, about one quarter will return.

1952

The Vancouver Japanese Language School re-opens on Alexander Street, the only building to be returned to the community following the war.1954

The Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association is created to help facilitate the rebuilding of the Nikkei community in British Columbia. The first constitution was drawn up February 20, 1954, and the society was formally incorporated on December 18, 1985.

1958

April The first issue of The Bulletin is published by the Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association in Vancouver. The bilingual publication serves the Japanese Canadians who have returned to the coast.

1958 - 2000

Nipponia Home the first Japanese Canadian Seniors home in Canada opens in Beamsville, Ontario. Founder Yasutaro Yamaga personally donated $25,000 which along with $27,000 from 853 Japanese Canadian donors and partnerships with the Lincoln community and the province of Ontario, enabled the establishment of the home. Other Issei founding members were Toyonori Namba, Takashi Komiyama, Tomiyo Uyehara and Takaichi Umezuki.

The grounds of Nipponia Home were renowned for their gardens, reflective of traditional Japanese landscaping practices. Both Japanese and Canadian meals were served daily, making it an early model for culturally appropriate care. In 1993 the Japanese Redress Foundation contributed a grant of $350,000 for renovations. When the home closed, funds were then directed to other Ontario Seniors facilities and programming. Photo of the Letters Patent.

1964

Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre opens in Toronto.

1967

Canadian government announces new immigration regulations—a point system for selection. It no longer uses race as a category.

Nikka Yuko (Japan-Canada Friendship) Garden is established in the city of Lethbridge to celebrate the Canadian Centennial.

1969

David Suzuki receives the Steacie Memorial Fellowship for the best young Canadian scientist. The Japanese Canadian geneticist spent his early life in a World War II detention camp. He was awarded his PhD in 1961 at the University of British Columbia. Though there were restrictions on Japanese Canadians from entering the professions, the civil service and teaching until 1967, Suzuki becomes Canada’s most popular and highly regarded scientific educator.

1973

June 19 Genzo Kitagawa is appointed to the Order of Canada for his leadership of the Japanese Canadian community in Saskatchewan and for his many contributions to the welfare of others.1974

November Needs Study of Senior Citizens Housing and Community Facilities in British Columbia submitted to Greater Vancouver JCCA

Tonari Gumi, the Japanese Community Volunteers Association, is founded. With the support of the local Japanese Canadian community and the federal government’s Local Initiative Program, Tonari Gumi develops its basic services for seniors. After originally working out of office space provided by the Downtown Eastside Residents Association (DERA), Tonari Gumi opened a drop-in centre at 573 East Hastings in 1975, and developed many of their current programs and services.

1975

September Japanese Canadian Society of Greater Vancouver for Senior Citizens Housing incorporated.

1976

July Property for Sakura-so seniors housing is purchased on Powell Street

August Kelowna Japanese Canadian Community Senior Citizens Association incorporated.

December 15 geneticist David Suzuki is appointed to the Order of Canada. A geneticist of international reputation who has succeeded in making science understandable and exciting to the layman through his lectures, and radio and television programmes.

December 15 Masajiro Miyazaki, is appointed to the Order of Canada. The retired osteopath, over a period of 35 years, gave unselfish service to the residents of Lillooet, British Columbia, particularly those of Japanese and Indian backgrounds, even through in ill health.

Ken Adachi’s book, The Enemy That Never Was: A History of the Japanese Canadians, is published by McClelland & Stewart, a seminal book that documents the historical racism against Japanese Canadians from 1877 to 1975.

Japanese Canadian Centennial 1977

Japanese Canadians renew national community ties by celebrating the centennial of the arrival of Nagano Manzo, the first known Issei in Canada. The centennial celebrations are closely followed by the organization of informal groups to discuss seeking redress.

The first Powell Street Festival takes place at Oppenheimer Park in Vancouver’s downtown eastside, the pre-war home of the Japanese Canadian community.

Barry Broadfoot’s book, Years of Sorrow, Years of Shame: the Story of the Japanese Canadians in World War II, is published. The book chronicles the history of the Japanese Canadians in WW II, as well as their arrival in Canada, and dispersal after the war, through the use of extensive oral histories. The end result is a detailed history of the Japanese in Canada from 1877 into the future told largely in the words of survivors.

1978

January 11 Artist, teacher and writer Roy Kiyooka is appointed to the order of Canada in recognition of the quarter century and more which he devoted to art in various forms, especially painting. His work is in Canadian collections from coast to coast and has been included in major exhibitions abroad.

Takeichi Umezuki is appointed to the order of Canada. The publisher of The New Canadian, a Toronto newspaper printed in Japanese and English, for nearly sixty years he devoted himself to the welfare of Canadians of Japanese origin.

July 4 Thomas Shoyama receives the Order of Canada. The first Japanese Canadian to have become a deputy minister, first of Energy, Mines and Resources, then Finance, he began his career as a labourer in British Columbia during the War Measures Act. Later, in Saskatchewan, he became economic advisor to the premier, T.C. Douglas, at a time when major social programs were being developed and in 1964, headed the Economic Council of Canada.

July 4 Tsutae Sato is appointed to the order of Canada. Honorary principal of the Vancouver Language School. In recognition of half a century spent in teaching his native tongue to Japanese Canadians and of his enriching Canadian society by the introduction of the best elements of his own culture.

November 5 Sakura-so, a home for Nikkei seniors, opens on Powell Street.

The Japanese Canadian Centennial Project publishes A Dream of Riches, a photographic history of the Japanese Canadian community. The photographs are also gathered together as a traveling exhibit that tours the country.

The Momiji Health Care Society (Momiji) established as a charitable organization for the Issei – the first generation of Japanese immigrants who came to eastern Canada, specifically those who settled in the Toronto area post WWII. It is the realization of a vision shared by its founders Mary and Roger Obata, Kazuo Oiye, Roy Shinobu, Fred Sasaki and Dr. Fred Sunahara. In 1992 with the help of a $1.2 million grant from the Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation the doors opened at the newly constructed Momiji Centre. The largest facility for Japanese Canadian Seniors in Canada.

1979

July 25 Five climbers reach the peak of Mt. Manzo Nagano, overlooking Lake Owekino near the head of Rivers Inlet some 250 miles north of Vancouver. The peak, named for the first Japanese immigrant to Canada, was designated in 1977 by the federal government to commemorate the Japanese Canadian Centennial. The climbers—three great-grandsons of Manzo Nagano, a brother-in-law, and a friend—first had to take a float plane from Port Hardy to Lake Owekino, cross canyons to the mountain base through heavy undergrowth, then make the arduous climb 6,600 feet to Mt. Nagano’s peak, there to implant a flag of Canada and leave a plaque and family crest. The journey took five days to complete. It is believed to be the first time the peak has been conquered. Lincoln Beppu of Seattle, who had fished the famed Rivers Inlet area, provided the environmental data. Members of the party were James and Stephen Nagano, sons of Dr. Rev. Paul M. Nagano of Seattle; David Nagano, son of Mr. & Mrs. Jack Nagano of Los Angeles, and their son-in-law Bob Drescher of Oxnard, Ca., and R.J. Secor of Pasadena, Ca.

August Hinode Home opens in Kelowna.

Inspired by a performance by the San Jose Taiko Group at the Powell Street Festival, a group of Asian Canadians form Katari Taiko—the first group of its kind in Canada. Katari Taiko goes on to inspire the formation of groups across Canada.

1980

The National JCCA becomes the National Association of Japanese Canadians (NAJC).

1982

June 21 Hide H. Shimizu is appointed to the Order of Canada. During the Second World War, she played a vital and voluntary role in ensuring that Japanese Canadian children in British Columbia received a proper education by organizing schools in camps and by supervising teacher training. After the war, she assisted in the social adjustment of Japanese evacuees in Toronto. Over the years she was also committed to church and community affairs.

1983

June 20 Judo master Yuzuru Kojima is appointed to the Order of Canada. One of Canada’s leading masters of judo, he received his black belt at nineteen and became a leader in judo organizations and a delegate to the Canadian Olympics Association. He is the first Canadian, and the youngest in the world, to have received the International Judo Union ticket.

Joy Kogawa’s novel Obasan is published by Penguin Books. Based on the author’s own wartime experience with her family in British Columbia & Alberta, it is the first book to tell the story—through fiction—of what Japanese Canadians went through during and after the war.

1984

December 17 Yutetsu Kawamura is appointed to the Order of Canada. In his half-century as a Buddhist leader he worked for the integration of Japanese-Canadians into southern Alberta society. Notable among his accomplishments is the Nikka Yuko Garden, which was Lethbridge’s Centennial project and is considered one of the best Japanese gardens outside Japan.

Art Miki becomes president of the NAJC and begins a concerted campaign for redress.

A brief entitled Democracy Betrayed: The Case for Redress is presented to the government on November 21. Attempts to negotiate with a series of ministers over the next four years are unsuccessful, but a strong case for redress is built in the community and the public.

1985

August 3 The light atop the Japanese Canadian War Memorial is relit during a special ceremony, almost 45 years after it was extinguished. The guest of honour is Sergeant Masumi Mitsui, the last surviving World War I veteran.

December 23 Architect Raymond Moriyama is appointed to the Order of Canada. The Toronto architect has won many honours for his functional yet aesthetically pleasing designs.

This is My Own: Letters to Wes and other Writings on Japanese Canadians, 1941 – 1948 is published. Based on a series of letters between Muriel Kitagawa and her brother Wes Fujiwara and edited by Roy Miki, the book is an eloquent portrait of a turbulent time in Canadian history. Muriel Kitagawa died in 1974 and Wes Fujiwara died on November 6, 2000.

1986

June 23 Writer Joy Kogawa is appointed to the Order of Canada. Her first novel, Obasan, a moving and eloquent account of the treatment of Japanese-Canadians interned during World War II as seen through the eyes of a five-year old girl, earned her several literary awards and provided Canadians with an important document relating to a critical period in their history.

1987

December The Nikkei Voice is launched as a bi-monthly publication by the Nikkei Research and Education Project of Ontario.

December 21 Robert Yasuharu Kadoguchi is appointed to the Order of Canada. He made a great contribution towards the mutual understanding between the people of Japan and Canada through his efforts within a number of multicultural organizations and as Founding President of the Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre, which not only caters to the needs of the Japanese community in Toronto, but also actively supports the activities of many other ethnic groups.

Redress & Beyond

1988

April 14 500 Japanese Canadians rally on Parliament Hill in support of redress. Many prominent Canadians come out to support their cause and the new Minister of State for Multiculturalism, Gerry Weiner, makes a statement that opens up dialogue with the community.

July 21 The War Measures Act is repealed.

September 22 Prime Minister Brian Mulroney announces a Redress Settlement negotiated between the National Association of Japanese Canadians and the federal government, to acknowledge injustices against Japanese Canadians during and after World War II, provide a payment of $21,000 to all Japanese Canadians affected by the provisions of the War Measures Act, expunge criminal records of those charged with offenses stemming from violation of provisions of the War Measures Act, re-instate citizenship of those exiled to Japan, establish a $12million community fund to help rebuild community infrastructure, and provide $24million, half in the name of the NAJC and half in the name of the government, to establish the Canadian Race Relations Foundation.

The Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation is established to administer the community funds. Over the next ten years, projects initiated across Canada include community centres and other facilities, cultural and artistic projects, and educational projects.

April 19 Art Miki is appointed to the Order of Canada. A Winnipeg schoolteacher by profession, he has been involved in many educational initiatives and has also played an active role in multicultural organizations at the local, provincial and national level. As the President of the National Association of Japanese Canadians, he was a respected spokesperson during the negotiations for redress for Japanese Canadians

November 1 Arthur S. Hara is appointed to the Order of Canada. A distinguished Vancouver business leader, he has contributed to his city’s cultural community, the nation’s economy and the global marketplace.

The Canadian Embassy in Tokyo, designed by renowned Canadian architect Raymond Moriyama, is officially opened with a solo performance by Vancouver pianist Jon Kimura Parker. Edith Terry of The Globe and Mail says, “There is something extraordinary in Moriyama’s attempt to come up with an architectural fusion of two countries as opposite as Canada and Japan, one a culture of open spaces, the other of intense formality and microscopic precision.”

1992

April 30 Juhn A. Wada is appointed to the order of Canada. An internationally respected neuroscientist and Professor at the University of British Columbia, he has devoted his career to research into the cause and treatment of epilepsy.

The Homecoming conference brings together four generations of Japanese Canadians from across Canada on the 50th Anniversary of the internment. It is a reunion of sorts for the issei and nisei, and a chance for the post-war generations to gain a deeper understanding of what it means to be Japanese Canadian.

The National Nikkei Heritage Centre Society is incorporated. The Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation grants $3.0 million for heritage centre project.

The National Film Board of Canada releases Minoru: memory of exile, an animated film by Montreal-based animator Michael Fukushima based on the experience of his father during World War Two.

The Last Harvest, a film by Linda Ohama is released. The film chronicles the family farm in Ranier, Alberta.

Work begins on the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre in New Denver, spearheaded by the Kyowakai (working together) Society.

The Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre opens in Steveston.

Kikyo, Tamio Wakayama’s photographic chronicle of Vancouver’s Powell Street Festival is published by Harbour Publishing. The book uses photographs and text to illustrate the emergence of a distinctive Japanese Canadian culture from the Centennial celebrations of 1977.

The Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japans Hall launches Year 2000 project. In 1994 the adjacent corner property is purchased, returning the property to its pre-war size.

1993

April 22 Irene A. Uchida is appointed to the Order of Canada. Professor emeritus of paediatrics and pathology at McMaster University, where she directed a model laboratory for more than twenty years, she has helped set high standards for cytogenetic laboratory diagnostic services in Canada.

August 12 Grand Opening of Momiji Gardens at the Pacific National Exhibition, commemorating the place where Japanese Canadians were processed before dispersal from the west coast.

September 27 The Japanese Canadian Redress Foundation presents a cheque for $2.5million to the National Nikkei Heritage Centre Society.

Landscape artist Takao Tanabe is awarded the Order of British Columbia. He has painted and studied in Winnipeg, New York, England, Italy, Denmark and Japan. He has served as head of the art department at the Banff School of Fine Arts and has also served on juries and committees at the National Capital Commission and Canada Council.

1994

June 25 Grand opening of the Gulf of Georgia Cannery in Steveston as a historic site on the 100th Anniversary of the cannery.

July 23 Grand opening of the Nikkei Internment Memorial Centre in New Denver.

September The Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association moves from its long-time home on Powell Street to its new home at 511 East Broadway in Vancouver. The building also houses the Japanese Canadian National Museum and Archives and serves as an interim home for the National Nikkei Heritage Centre.

November 5 Grand Opening of the Kamloops Japanese Canadian Cultural Centre

Japanese Canadians in the Arts, a Directory of Professionals, coordinated by Aiko Suzuki, is published by the Toronto Chapter of the National Association of Japanese Canadians.

1995

Tomko Makebe’s book, Picture Brides, originally published in Japan in 1983, is translated by Kathleen Chisato Merkin and released in Canada by the Multicultural History Society of Ontario. The book tells the story—through their own words—of five women who came to Canada as picture brides in the early 1900s.

The Japanese Canadian National Museum & Archives Society is incorporated and begins planning for museum and archives facility in new National Nikkei Heritage Centre (NNHC).

Geneticist David Suzuki is awarded the Order of British Columbia. Through his popular television series The Nature of Things, the CBC radio series Quirks and Quarks, as well as his numerous books, Dr. Suzuki has brought the concept of living within the planet’s productive capacity for a sustainable future into our homes and our consciousness.

1996

The Canadian Race Relations Foundation is established.

The Census of Canada shows a Japanese Canadian population of 77,130, of whom approximately one third indicate multiple ethnic backgrounds, indicating an intermarriage rate of over 90% in recent decades.

1997

August 24 To mark the 120th anniversary of the first Japanese to settle in Canada, a group of climbers led by NAJC President Randy Enomoto climb Mt. Manzo Nagano and leave a time capsule at the summit. Of the 11 expedition members, four are direct descendants of Manzo Nagano.

1998

July 4 Opening ceremony of New Sakura-so seniors housing complex, the first component of Nikkei Place, at Kingsway and Sperling in Burnaby.

July 22-26 A four-member team attends the PANA Nikkei International Sports Fellowship in São Paulo, Brazil, returning with three gold medals, three silver, and one bronze.

Keiko Miki becomes the first woman president of the NAJC.

Kazuko Komatsu is awarded the Order of British Columbia.

1999

March 26 Groundbreaking ceremony for the National Nikkei Heritage Centre at Kingsway and Sperling in Burnaby.

April 15 Pianist Jon Kimura Parker is appointed to the Order of Canada. A gifted pianist, Jon Kimura Parker has played in some of the world’s most prestigious venues. In addition, he has given unique, personal concerts in remote communities across Canada.

April 15 Painter Takao Tanabe is appointed to the Order of Canada. Tanabe is a talented landscape artist and an influential teacher of younger generations of Canadian artists.

August 15 A monument is unveiled at Ross Bay Ceremony is Victoria by the Kakehashi Group. The common monument honours the 150 Japanese Canadians buried at the cemetery. The first is Yoshitaro Muneyama, age 26, January 11, 1887. Included among the dead are Manzo Nagano’s first wife, Tsuya, and their infant daughter.

2000

June 25 Grand opening of the new Vancouver Japanese Language School and Japanese Hall at 475 Alexander Street. The building is designated a historic site by the city of Vancouver.

July Team 2000, a hockey team made up of young players of Japanese descent, heads to Japan to attend a National Midget Camp and play against Japanese teams.

September 22 The National Nikkei Heritage Centre officially opens in Burnaby, BC. The occasion also marks the opening of the Japanese Canadian National Museum and its inaugural exhibit, Reshaping memory, Owning History, Through the Lens of Japanese Canadian Redress. The Centre houses the National Nikkei Heritage Centre Society, the Japanese Canadian National Museum, the Japanese Canadian Citizens’ Association, the Nikkei Seniors Health Care and Housing Society, ICAS Nikkei TV, the Gladstone Japanese Language School, and the Japanese Immigrants Association.

October 29 The Britannia Heritage Shipyard in Steveston is declared a National Historic Site.

November 15 Arthur Tsuneo Wakabayashi is appointed to the Order of Canada. A career public servant, he served provincially as Deputy Minister of Finance and Deputy Provincial Treasurer, and also federally as Assistant Deputy Minister to the Solicitor General and Economic Development Coordinator.

Engineer Henry Wakabayashi is awarded the Order of British Columbia. Wakabayashi had a key role in some of British Columbia’s most important public projects and was also instrumental in the construction of the Momiji Gardens and the National Nikkei Heritage Centre.