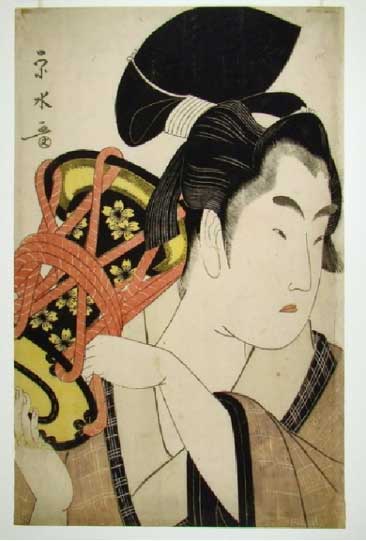

Wakashu with a Shoulder Drum

Hosoda Eisui (active 1790–1823)

Sir Edmund Walker Collection

A Lecture by Dr. Asato Ikeda @ Chang Yu Tung East Asian Library at U of T, October 12, 2016

by David Fujino

On October 12th, Dr. Asato Ikeda delivered an engrossing lecture on A Third Gender, the ground-breaking print show she curated at Toronto’s ROM (Royal Ontario Museum). The ROM show opened in May and ran until November 27, 2016.

For much of the audience this October afternoon, it was high time the full range of ukiyoe prints — meaning the shunga (erotic) prints — were finally pulled out of the ROM’s Japanese art collection and brought to light. The crowning irony was that the august and family-oriented ROM (some have quipped, ‘Victorian ROM’) should be the generator of a serious conversation about gender, sexuality, and alternative lifestyles — but there you have it, and we had Dr. Ikeda to thank for finding the 60 shunga prints. This show was inspired by previous shows at the British Museum and the Honolulu Museum of Art.

A Third Gender is the first North American display to focus on wakashu, the male youths of Edo-period Japan (1601-1868). The wakashu, aged 15 to 18 years, were the object of desire for both men and women. Wakashu played distinct social and sexual roles, and were considered a third gender, women were considered a fourth. In actual fact, there were many genders four hundred years ago in Edo-period Japan.

While many of these prints are definitely elegant, they don’t represent the highest level of ukiyo-e artistry: their core value lies in the information they convey about life in Edo Japan; for instance, although wakashu were often indistinguishable from women — except for the small shaved spot on top of their heads — they also wore no hairpins or decorative combs in their upswept hairdos.

Also, woodblock prints were a product of Edo (later Tokyo), the big city of the time, and they’d been produced collaboratively since the 8th century by a designer, engraver, printer, and publisher, and were sold for the delectation of the samurai, monks, and merchant classes, not for the rural and farming classes. To set the record straight on their artistic worth, the exhibit’s prints were created in the early 18th to mid- 19th centuries by major ukiyo-e masters, including Okumura Masanobu, Suzuki Harunobu, and Kitagawa Utamaro.

Dr. Ikeda also noted that in Edo-period Japan, the sexual culture was radically different from ours. Strict Confucian values defined gender expression, and sexual identity was as much about social standing and age as one’s biological gender. Adult males could have sex with both wakashu and women, who were separated into married and unmarried, prostitutes and courtesans. And Kabuki theatre popularized wakashu, and the onnagata played women — a prime example of this living tradition is Tamasaburo Bando, a contemporary onnagata of considerable acclaim. So we learned that sexual expression and sexual identity were very much a social construct.

And lest we rush too quickly to celebrate the pan-sexual fluidity of these Japanese youths, we should be reminded that since Japanese society did not operate under the Judeo-Christian concept of original sin, the habitués of Edo freely enjoyed pleasures of the flesh without shame. Men visited prostitutes and looked at shunga prints, of which there were quite a number of graphic examples in Dr. Ikeda’s show. The point is that Edo-period Japan was its own distinct and separate kind of cultural island within Japan.

In her catalogue essay, Dr. Ikeda noted that same-sex images were excluded from her exhibit because of concerns about the age of ROM viewers. In the Edo period, life spans were shorter, and those who’d reached puberty were expected to be sexually active, so age of consent was never an issue.

How this differs from the moral influence of Western powers during Japan’s modernization in the 19th century! The adoption of a binary (male-female) gender structure and the primacy of heterosexual relationships as ‘normal’ led — as Dr. Ikeda stresses — “to the disappearance of gender and sexual diversity in many cultures.”

During her lecture, Dr. Ikeda often said historical records about Edo-period Japan were lacking. This was certainly frustrating enough to hear, but with this frustration came the poignant realization that we’ll never really know what the wakashu thought and felt about their own lives.

Dr. Asato Ikeda is an Assistant Professor of Art History at Fordham University and specializes in art, war art, and fascism.